Yeri belongs to the Torricelli family of languages, which comprises approximately fifty languages and around 80,000 speakers. The Torricelli family has a number of branches, but since these are currently far from certain, we shall not discuss them here.

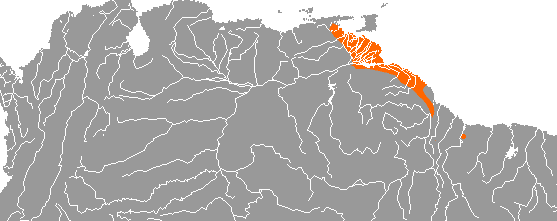

The Yeri language is spoken in only a single village in the Sanduan Province of Papua New Guinea.

Our story here is called The bad-skinned snake kills a woman, and was recounted by Josepa Yikaina. It did not have a Yeri title, so I created one.

Yotu nogual oden harkanogɨl = The women and the snake

- Ta mnobia yuta nogual wiai.

- Lawiaki atia miakual. Atia miakual anor wul.

- Aro aro wuakɨr tɨhewo. Tei atrei sasapiten, o wul.

- Amotɨwai amotɨwai amenor lelia.

- Aro ŋa wakia woli ŋa wakia woli.

- Aro woimewɨl wdolkɨdi sareiga. Iepoua harkanogɨl.

- Harkanogɨl losi weide yiwo wiluada.

- Wohewɨl walia wamenor lelia.

- Wanor lelia te hamote, luten dawowa hagɨl.

- Luten wlopen. Dawowa hagɨl.

- Harkanogɨl yotu psia war wamena. Wgamera luten ndodi hagɨl wde.

- Wnobiada “haraharahi, ye ko nɨtren maŋan nbanokɨl?”

- Te wnobia “hiro ya, hiro ya, lolewa hiro. Miakual nadɨ.”

- Harkanogɨl namenia lutei. Worme mani. Yawi wden psia warma.

- Wnobiada, “haraharahi. Harkanogɨl kɨ nanor norme hamaul wye.

- Hem ta hiro mɨlmkialen, hiro.”

- Aro psia ar tɨnogɨl. Amo wul wo weli.

- Ameyaka te woheka, hiro.

- Wormia goimabɨ lapaki. Amenodai olbɨl yo.

- Nobia ta amotɨwa harkanogɨl almkialen, hiro.

- Noimo ni weide, noimo nonemo, wan wde.

- Hamote yuta walmo wodɨ harkanogɨl.

- Ode ormia aro gamerade.

- Aro yotu hepa. Pɨrsakai tiawa laladɨl nadɨ.

In English:

- I will talk about two ladies.

- A long time ago they looked for frogs. They looked for frogs downriver.

- They went all the way downriver. They saw many of them in the water.

- They caught and caught them and put them down into the limbum.

- They went and one walked on one side of the river and the other walked on the other side.

- She went and she got them, she shook the box. They were all around the snake.

- The snake’s name is Bad Skin.

- She grabbed it, and threw it down into the limbum.

- It went in the limbum of the woman who had a big sore on her back.

- It was a big sore. It was on her back.

- That snake comes out. It digs at the sore on her back.

- She said, “Friend, you look at it. What bit me?”

- The friend replies, “No, no, there is nothing there. It’s only frogs.”

- The snake is going inside the sore. It is sleeping inside. Only its tail is coming out.

- She said, “Friend. The snake has already gone down and is lying in your stomach.”

- I won’t pull it out, no.”

- They arrived at the village. They boiled some water.

- They give it to her and she drank, but no.

- She sits and breaks the tongs. They push them inside the hole of the sore.

- They want to catch the snake and pull it out, but no.

- It eats her intestines and eats her heart.

- That lady died with the snake in her.

- They sit with her and they went to bury her.

- That’s all. The story is very short.

- Not only is this story very short, but it is actually a streamlined version of the original. The section I removed is not very long, and does not affect the overall meaning of the story. Essentially, the woman asks her friend whether there is a snake, and she says no. She asks again, and this time she can see it. They do this at intervals on their walk back to the village.

When they reach the village, they first inform the soon-to-be widower of his wife’s condition, before proceeding with their attempts to kill the snake.

- Speaking of the snake, although harkanogɨl refers to snakes in general, does this story refer implicitly to a particular species?

After consulting both Wikipedia and the Reptile Database, I have arrived at the educated guess that harkanogɨl refers to the species Toxicocalamus buergersi, also known as the Torricelli Mountains snake.

Since Yeri is spoken in that same mountain range, this is my first point of evidence.

- My second line of proof arises from the text itself. To quote line 6:

Iepoua harkanogɨl. = They were all around the snake

But why are the frogs mentioned at all in the story, considering their meagre impact on the story as a whole? Would the story still make as much sense if they were foraging for berries or nuts instead?

Well, we can answer this if we look at the snake itself. I have included a link to the Reptile Database itself, and I am sure you’ll agree that it bears a resemblance to a certain residence at the bottom of your garden, one whose initials are W.W.

Another similarity between the two is that both of these individuals are fossorial in nature, which means that they dig through soil and mud in order to gain their sustenance.

An aspect wherein they diverge is their sleep patterns: while T. buergersi is diurnal (the opposite of nocturnal), W.W. takes no heed of the sun’s behaviour as it regards his wiggling.

For anyone raised outside of England (and, I assume, other parts of the Anglosphere), T. buergersi looks like a worm, thus explaining why the frogs took an interest in him. Furthermore, members of the genus Toxicocalamus tend to be quite small, with the largest specimen, Toxicocalamus ernstmayri, measuring just above a metre from snout to vent.

(As will be discussed in the Translation Analysis, snakes in Yeri tend to be Masculine.)

- This leads us to the question as to whether miakual could also refer to a specific sort of frog. I would wager that it belongs to the family Microhylidae. This family constitutes the majority of frogs found in Papua New Guinea, and thus it seems a reasonable guess.

In truth, I did not consider it particularly important to determine the species of the frog, since they are not overly important to the story.

- My last thought on the frogs is the purpose whereto the women have chosen to collect them. My first thought was that frogs were a traditional (or perhaps even contemporary) Yeri cuisine.

Then it occurred to me that perhaps these frogs had a role in traditional Yeri medicine. This may be more likely since the Torricelli Mountains contain creatures with much greater protein content.

Meanwhile, a somewhat more unorthodox hypothesis is that the Yeri may have used these frogs in a manner similar to that of certain South American tribes. Personally, I find this unlikely because most of the Papuan frogs I have seen have colours that blend into the environment.

(This comes from a cursory glance at the list of pictures on the Ecology Asia website. This cannot capture every frog species that calls Papua New Guinea home, but it is a start.)

Poisonous frogs, on the other hand, tend towards bright, garish colours that contrast as much as possible with their surroundings. This is in order to scare away predators, since being poisonous brings zero benefit if no-one knows to avoid eating you.

- Last, but most importantly, what is the purpose of this myth? To what perennial truths does it allude?

Put simply, this appears to be a cautionary tale about the fauna of the Torricelli Mountains, in particular the amphibians.

As creatures that live in the water and on land, frogs and toads are in excellent position to act as a transit for water-borne parasites, which can enter through open sores, as well as via ingestion.

(Although the Guinea Worm is not, to my knowledge or research, present in Papua New, the bit where the snake’s tail is hanging out very much reminds me of how the worm is coaxed out of the poor victim’s foot.)

Indeed, the end of the story, where the tongs and hot water fail to kill the snake, probably comes from previous trial and error.

Thus, it is not unreasonable, I feel, to perceive this story through an educational framework.

On a tangent, a detail that I left out is that the woman with the snake inside her was married. This could, in context, indicate that she was pregnant. If one takes this reading, then it may be used to impart that pregnant women are more vulnerable to malign parasites; certainly in terms of effects, but perhaps they are also more attractive to them.

(This makes me wonder whether the Yeri, or related tribes, have taboos against pregnant women engaging in certain sorts of foraging mission.)

Warray was a language once spoken along the Margaret and Adelaide Rivers in the Northern Territory of Australia. It belonged to the Kunwiñkuan language family, with its closest relation being Jawoyn.

Especially unfortunately, before Harvey was able to record is grammar, the language had undergone a significant degree of vocabulary loss, although grammatical structures appear to have escaped relatively unscathed.

Nevertheless, we are here to celebrate the language and its stories as they were, so let us dive straight in.

In this chapter, we will in fact, cover two versions of the same story.

Original Text:

Awananaŋku Antjeriñ

- Altumaru yuŋuyiñ puk:aniñ.

- Tjatpulayi kuntiyiniñ anwak mamam akalawu katjiyaŋ altumaru pulmiñ.

- Altumaru pokliliñ puñi anpik pulam.

- Tjatpula yatjiñ puk:aŋi tjitpak:u wayiñ ñiliñ tjipak.

- Punwuy mamam akalawu keraŋlul wuyi anpik natlakiñ.

- “Yañ” altumaruyi tjiyi akalawu.

- Wuyi.

- Anpik mi katjiyaŋ molwikyi tañmi.

- Tjatpula liñ.

- Anpik altumaruyi tañmi milwikyi.

- Amukuy liñ tjatpula katji awananaŋku katji liñ.

Awananaŋku Keraŋlul

- Tjatpula awananaŋku waŋu puk:aŋi.

- Yatjiñ lam pikiriŋu tjipak.

- Luramiñ leriklik.

- Mamam alkalawu keraŋlul paniniñ leriklik.

- Antjeriñwuy mi.

- Pakuntiyiniñ antjeriñ almutek.

- Katjiyaŋ altumaru wayiñ punnay.

- Punnay.

- Neŋkiñ mi.

- Puñi tañmi pokliliñ pulanu anpik anpuruyu.

- Katjiyaŋ tjatpula yatjiñ kawuy.

- Kawuy wayiñwuy katjiyaŋ nattañmi.

- Tjatpula katji liñ ŋumpwaruwat.

The English Translation:

Awananangku One

- The old woman used to go out hunting for tucker.

- While she was out, the old man used to play around with his daughter, which caused the woman to become angry.

- The old woman rubbed banyon tree fibres and made a rope.

- The old man went out hunting for fish, which he would bring back with him.

- He gave the fish to his two little daughters, and clumbup the rope that the old woman had dropped towards him.

- “Come up” the old woman said to him.

- He clumbup.

- He grabbed the rope and then the old woman cut it with a mussel shell.

- The old man fell.

- The old woman cut the rope with a mussel shell.

- Okay, he fell, that old man, Awananangku, that one fell.

Awananangku Two

- The old man Awananangku went out hunting for meat.

- He speared some fish for his daughters.

- He brought them back to camp.

- Her (the old woman’s) two daughters were sitting in the camp.

- He got one of them.

- He played around with the big one.

- The old woman came back and she saw them.

- She saw them.

- Then she got, oh what are they called.

- Banyon fibres, she cut them and tied them into a long rope.

- Then the old man went out again.

- Then he came back again and this time she cut the rope on him.

- That old man fell forever.

- In contrast to the all of the previous tales discussed, this one does not require some detective work on my part to figure out the meaning of this story. Harvey provides it for us directly after the story.

Rather than re-invent the wheel, as it were, I will quote him verbatim:

“These two versions of the same story are concerned with the Milky Way. The old man, the old woman and their two daughters lived in the Milky Way. As the two versions recount, the old man had illicit sexual relations with his [eldest] daughter while the old woman was out hunting. The old woman came back and saw him misbehaving ad became angry.

When the old man went out hunting again, the old woman made a rope from banyon fibres. The old man came back with fish and the old woman lowered down the rope so that he could climb back up to the Milky Way. While he was climbing the old woman cut the rope with a mussel shell. The old man made a hole, next to the Southern Cross on the pointer side, in the Milky Way as he fell.

He hit the ground at a banyon tree near Humpty Doo camp called Awananangku. This story explains why the Milky Way is called Anpik[, or] ‘rope’.”

- Many of you will notice a similarity in etymology. In Warray, our native galaxy is referred to as Anpik because of the rope that sent the old man tumbling back down to Earth.

In English, we call our galactic home the Milky Way because of Heracles who, as a child, spat out his mother’s breast milk across the sky.

- This is not the only Warray myth, recounted by Harvey, which involves an old man, an old woman and two daughters. It is called: “The Old Woman and Old Man Dreaming”, and I shall give you the English version:

“The old woman, a mother and her (two) daughters, they both went down to the saltwater. The old man came from there, from Titi to the saltwater. He saw them both (the mother and the daughters). Then they came this way to Loliwa. They both came out (of the water), they both came. Then they (all) followed the one road. They went down (further) and are now staying forever at Tjetteriñ.”

- This story describes the complex journey of several dreaming trails centred around the Adelaide River. The woman and her two daughters begin at Scott’s Creek and go to Malweyi, which is on the eastern side of the river.

The old man, meanwhile, starts at Titi, which is at the mouth of the Adelaide, and journeys upwards. (His exact starting point is Natiyañku, or Old Man Rock, which lies in the middle of the river’s mouth.)

Together, they travel to Loliwa on the western side of the river, and further on to Tjininti, also known as Mosquito Pass, where the two daughters decide to stay.

The old man and old woman, on the other hand, make a journey to Tjettjeriñ ridge, which forms the eastern side of Manton Dam. On the way they walk through Alawarr ridge (The Daly Range), Kwik:i (Fred’s Pass) and Palankanaŋ creek (Manton River).

At Tjettjeriñ range there is a red ochre deposit, a cave or a site in general, where they might still be found to this day, possibly waiting for Warray speakers who will never come.

- Anyway, why do I mention this?

It is not my intention to posit whether the participants in this story are the same as in the other one, because personally I find this unlikely. In one story, only the old man is sent back to earth while the three women remain in the Milky Way, while in the other, all four people make separate homes on Earth.

- But could the old man be the same in both stories, with Natiyañku being the sequel to Awananaŋku?

This is not impossible, but I do not have enough textual evidence to prove it definitively. A brief gander at the relevant maps shows that Humpty Doo lies relatively close to the mouth of the Adelaide, so the journey from Awananaŋku to Natiyañku is a plausible one.

However, what is interesting is that both stories end with the word ŋumparuwat, which means forever.

- In addition, ŋumparuwat also finalises another myth, this being “The Three Dogs”.

This tale concerns three dogs, these being the husband and father Liyeyima, the wife and mother Wirminpul, and their son Wayinima.

Here, we witness again the recurring motif of man, woman and child.

- The motif of a close family unit appears in all three of the myths mentioned so far (as well as a few others). Nevertheless, it does not appear in the same way each time.

In Awananaŋku, we have a father, mother and two daughters.

In Natiyañku, we have a mother, two daughters and an unrelated man.

In Ŋiri Keraŋantjeriñ (lit. Dogs Three), we have a father, a mother and one son.

- In Ŋiri Keraŋantjeriñ, the age of the dogs is not specified, (indeed, it is not even specified in the text that they are dogs) but in Awananaŋku and Natiyañku, the mother is designated as altumaru and the father/man as tjatpula, which mean old woman and old man respectively.

I have some thoughts and musings on the significance and consequences of older parents, both in myth and real life, but that falls outside the scope of this article.

The Sheep and the Horses

- [On a hill,] a sheep that had no wool saw horses, one of them pulling a heavy wagon, one carrying a big load, and one carrying a man quickly.

- The sheep said to the horses: “My heart pains me, seeing a man driving horses.”

- The horses said: “Listen, sheep, our hearts pain us when we see this: a man, the master, makes the wool of the sheep into a warm garment for himself. And the sheep has no wool.”

- Having heard this, the sheep fled into the plain.

Sipsip Wodei Hosegal

1. Tutupi la sipsip hiro wul matrem hosegal, ŋan nalkialen nebalgi tiawai, ŋan narkiakan porpori wlopen, ŋan narkiakan ndarku hamoten.

2. Sipsip wnobiadam hosegal: “Wan whem wo weli, wnobiadan hamoten namotɨwam hosegal.”

3: Hosegal nobiawan: “Sipsip ida! Wan whebi o weli, nobiadan: hamoten, hamoten wlopen ndodia wul wde sipsip pade. sipsip hiro wul.”

4: Nomal wiedada, sipsip la wdarku wnania halma pebo.

The Sheep and the Horses:

- On a hill, a sheep that had no wool saw some horses: one of them pulling a heavy wagon, one carrying a big load and one carrying a man quickly.

- The sheep said to the horses: “My heart pains me, seeing a man driving horses.”

- The horses said: “Listen sheep our hearts pain us when we see this: a man, the master, makes the wool of the sheep into a warm garment for himself. And the sheep has no wool.”

- Having heard this, the sheep fled into the plain

Nentu waŋ anturk:u

1. Waŋ amala mitjayiwu punnay nentu kirilik: antjeriñ pamuñ akunkun yurmayim, antjeriñ tup:u amutek wukmayim, antjeriñ nal wukmayim kiyakyiwu.

2. Waŋ nentuwu puntjiyi: “Antwuy pankatjipum patnayu: nalyi nentu inpitjipmalañ.”

3. Nentu patjiyi: “Waŋ ŋa! Antwuy inkatjipum palinayu: nal, tjatpula, mitja waŋu kalilitpun anmewelu amalmal akalawu. amala waŋ mitja kankakaŋi.”

4. Kak:wuy nayu, waŋ wuppum kolallik

yuta nogual is built from two components. These are:

- yuta is a noun which means woman.

- nogual is a noun which indicates plural number, and is most commonly used with yuta.

yuta can also function as an adjective, where it means female.

nogual can also occur alongside the word hagɨl, which is the plural form of the word han, which means man.

oden is built from three components:

- Ø- is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Subject Prefix.

- ode is a verb which means to be with, but it also translates as and in many contexts.

- -n is the 3rd Person Plural Object Suffix.

harkanogɨl is the singular form of the noun harkanogɨ, which means snake.

The plural form, meanwhile, is harkanogɨi.

harkanogɨ is very much a base form of the noun, which does not appear in grammatical speech.

ta is the Future Tense Particle. It does not in specify the relative distance in the future wherein the event takes place, merely that it occurs after the moment of speech.

mnobia is built from two components:

- m- is the 1st Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- nobia is a verb which means to talk or to speak.

wiai is the Feminine form of wia, which refers to the number two.

For context, the Masculine form of wia is wiam

Yeri has two grammatical Genders: Masculine and Feminine.

For an exploration into how Gender works differently in Yeri compared to the languages of Western Europe, I refer you back to the original chapter on the language.

lawiaki is a noun which means a long time ago.

It is possible that this could be related to the Past Tense Particle la, but I do not have any evidence to make a claim one way of the other.

atia is built from two components:

- Ø- is the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- atia is a verb which means to see or to look at something.

The Yeri verb for to see actually has four roots, these being atia, atr, arnia and arr.

To quote Wilson, atia occurs when “there is neither a predicate morpheme nor a third person object morpheme.”

miakual is the plural form of the noun miakua, which means frog.

anor is built from two components:

- Ø- is the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- anor is a verb which means either to descend or to go down.

wul is a noun which refers to any body of water, e.g. a river or a lake, as well as water in general.

wul is classified as an Invariate Noun, which means that the Singular and Plural forms are identical.

As a result, the phrase anor wul, which receives here the translation downstream has the more literal meaning the waters descend.

aro is built from two components:

- Ø- is the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- aro is an alternate form of the verb ar, which means to go.

The repetition of aro indicates that they travelled a long while, in this context all the way down the river.

wuakɨr is built from two components:

- w- is the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- uakɨr is a verb which means to fall.

In Yeri, there are two Plural Subjects which take alternate Prefixes.

These are the 1st Person Plural, which takes the Subject Prefixes h- and Ø-, and the 3rd Person Plural, which takes the Subject Prefixes Ø- and w-.

tɨhewo is built from two components:

- tɨ- is the Yeri Locative Prefix, which occurs before a restricted class of nouns.

- hewo is a noun which beans bottom or ground.

A Locative Prefix, as the name suggests, indicates location, and can take English translations including on, in and at.

In addition to this, Yeri has three Locative Suffixes, though these only occur on fully-inflected verbs.

The pronoun tei is, in fact, built from two components:

- te is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Pronoun, also known as she.

- -i is the Plural Suffix.

In Yeri, there is no Gender distinction amongst the 3rd Person Plural Pronouns, as is the case in some Western European languages.

Not only does there exist the alternate form tem, but tei can also take the abbreviated form ti.

atrei is built from four components:

- Ø- is the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- atr is a variant of the verb for to see.

- -e is one of many Augmented Object Suffixes.

- -i is the 3rd Person Plural Suffix.

With many verbs, the 3rd Person Objects are constructed with the use of an Augment Suffix, which stands between the verb and the Object Suffix.

Other verbs take simply the regular Suffix, while a select few take an Infix instead.

sapiten is a quantifier which means many or a lot, and here it has undergone Reduplication of the first syllable.

Although it is composed of both a single syllable and a single letter, o has two components:

- Ø- is the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- o is a verb which means to stay in the sense of to be located in.

Other meanings of o include to live and to stay in the location.

It can also mean to be in general, but this verb works differently to the others.

amotɨwai is built from three components:

- amotɨ is the irregular Imperfective form of the verb otɨ, which means to hold something.

- -wa is another Augmented Object Suffix.

- -i is the 3rd Person Plural Suffix.

The Imperfective is roughly equivalent to the English Progressive –ing form. For example:

C – 1 ten la nor = He slept

C – 2 ten la norme = He was sleeping

The Imperfective indicates that the event was still ongoing during the specific period of time.

amenor is built from three components:

- Ø- is the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- anor is a verb which means to descend.

- -me- is the Imperfective Infix.

The Imperfective occurs most frequently after the first syllable of the verb wherewith it interacts. As most Yeri verbs have more than one syllable, it typically manifests as an Infix, but not always, as seen in the examples above.

The term limbum refers to a container made from the bark of the limbum palm, used in this story to carry frogs.

ŋa is built from two components:

- ŋa is the numeral one.

- -Ø is the Feminine Singular Suffix.

In addition, ŋa can also take the Masculine Singular Suffix –n and the Plural Suffix –i.

The resultant form ŋai occurs with Pluralia Tantum nouns, these being nouns which always trigger Plural Agreement on the accompanying adjectives, regardless as to actual number.

wakia is built from two components:

- w- is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Subject Prefix.

- akia is a verb which means to move in a particular direction.

woli is an invariant noun which refers to the side of a river or of a house.

woimewɨl is built from three components:

- w- is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Subject Prefix.

- owɨl is a verb which means to take something or to bring something.

- -me- is the Imperfective Infix.

By this point, you have probably long since noticed that w- can serve as the Subject Prefix for both the 3rd Person Feminine Singular and the 3rd Person Plural. I mention this now as I made that same mistake when I first wrote the vocabulary list.

wdolkɨdi is built from two components:

- w- is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Subject Prefix.

- dolkɨdi is an alternate form of the verb dorkɨdi, which means to shake.

sareiga is a noun which can refer to one of two things. These are a box hung above a fire to dry protein, and a large bird nest. I imagine that this double meaning originates from the shape and overall appearance of the drying box.

iepoua is built from four components:

- Ø- is the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- iepou is a verb which means to roll or to curl around, and it is often used to refer to the act of rolling tobacco.

- -a is one of the Augmented Object Suffixes.

- -Ø is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Object Suffix.

The phrase miakual iepoua harkanogɨl has a literal meaning of the frogs curl around the snake or the frogs roll the snake. However, it seems that the meaning has extended to mean the frogs surround the snake.

losi is an Pluralia noun which translates as name or names respectively, depending on context.

weide is built from three components:

- w- is called the Relational Prefix, which appears in a number of contexts, including the Genitive.

- -ei is the 3rd Person Plural Possessed Suffix, which means that more than one thing is being possessed.

- -de is the form that the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Pronoun te takes when building a Genitive (or Possessive) Pronoun.

Thus, weide by itself means something akin to her things.

The phrase harkanogɨl losi weide has a literal meaning of the snake her name, but this is how Yeri does possessives in general.

Thus, the closest English translation is the snake’s name.

yiwo is an Invariable noun which means skin.

wiluada is built from four components:

- w- is the Relational Prefix, which can also appear with some Adjectives as well as Genitives.

- ilua is an adjective which means bad.

- -da is the Bare Non-Verbal Pronominal Suffix.

- -Ø is the Singular Feminine Suffix.

Now, what exactly is a Non-Verbal Pronominal Suffix, and what does it do?

To be honest, this is where we reach the limit of both my understanding and capacity for explanation. In Yeri there is a complex system of Pronominal forms, and their behaviour.

Hopefully I will one day be able to understand and explain this particular area of grammar, but that day is not today.

wohewɨl is built from three components:

- w- is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Subject Prefix.

- owɨl is a verb which means to take something.

- -he- is the 3rd Person Feminine Singular Object Infix.

The Infixes are unique among the 3rd Person Object Affixes in the sense that the Singular Feminine is actually marked. When the 3rd Person Object takes the form of a Suffix, the Singular Feminine is indicated via its absence, whether it be unmarked or take any of the various Augmented suffix.

walia is built from three components:

- w- is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Subject Prefix.

- alia is a verb which means to drop or to throw.

- -Ø is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Object Suffix.

In her grammar, Wilson collected approximately 330 verbs, only 40 of which take Infixes. The rest take suffixes, but I did not find a distribution of Augment versus non-Augment Suffixes. In theory I could scan the dictionary and do the maths, but I have neither the time nor inclination to engage in such an exercise in pedantry.

wamenor is built from three components:

- w- is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Subject Prefix.

- anor is a verb which means to descend or to go down.

- -me- is the Imperfective Infix.

wanor is built from two components:

- w- is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Subject Prefix.

- anor is a verb which means to go down or to descend.

te is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Subject, also known as she.

It is the base whereon all other 3rd Person Pronouns are built.

hamote is built from two components:

- hamote is a noun which means individual.

- -Ø is the Singular Feminine Suffix.

hamote can also mean woman more specifically .

If we replace the second component with the Singular Masculine Suffix, we get hamoten, which means man.

The plural form of hamote is the irregular noun hamei, which also appears in a number of its own constructions, some of which feature in the original Yeri chapter.

luten is built from two components:

- lute is a noun which means sore or an open wound.

- -n is the Singular Masculine Suffix.

As mentioned earlier, Yeri takes a rather more relaxed approach to the assignment of Grammatical Gender, at least compared to the European languages with which you are probably more familiar.

dawowa is built from four components:

- d- is the Middle Use Prefix.

- awo is a verb which means, quote, “to set something down that has neither an overly long horizontal axis nor an overly long vertical axis.”

- -wa is one of Augment Suffixes.

- -Ø is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Object Suffix.

Now what does the Middle Use Prefix do?

Essentially, it turns a Transitive Verb into an Intransitive Verb which roughly means to be in that position.

For example, we have the verb awɨl means to hang:

C – 3 peigɨliai wahewɨl = Some hangs it (up)

C – 4 hɨwol wanagawɨl yotua wdawɨl = The breadfruit hangs there

In the former sentence, ahewɨl refers to the act of hanging something up, e.g. on a hook or on the wall, while in the latter, wdawɨl, or the breadfruit, is simply hanging there.

As a result, it can also take on a Reflexive meaning. luten, the sore, is both the thing doing the setting, and the thing being set on the back.

hagɨl is a noun which means back.

wlopen is built from three components:

- w- is the Relational Prefix.

- lope is a noun which means good.

- -n is the Singular Male Suffix.

In relation to both sentences, I have given dawowa the independent translation of it sets itself on her.

Now, you may be wondering why dawowa lacks a Subject Prefix.

I am also wondering this. Perhaps the answer is hidden somewhere in Wilson’s grammar, but I could not locate it.

Personally, I wonder whether luten dawowa should in fact read lute ndawowa, but because it appears twice in that form, I shall err on the side of caution and leave it as it is.

yotu is built from three components:

- yot is the Yeri Demonstrative, which has four functions.

- -u is the Middle Distance Suffix.

- -Ø is the Feminine Suffix.

All of the Yeri Demonstratives are built following this pattern. The Yeri Demonstratives have four functions, which fall into four categories:

- Nominal

C – 5 kɨ maŋa yotu? = What is that?

In instances where the gender of a noun is unknown, the Feminine form is used as a default.

Additionally, it is morphologically the simplest.

- Adnominal

C – 6 wonela yotun namena = That centipede is coming

yotun is built from three components, the last being the Singular Masculine Suffix –n.

wonela, meaning centipede, is considered a Masculine Noun.

In Yeri, the classification of Grammatical Gender follows a number of rules. For non-human animals, Gender is assigned in one of two ways.

If the biological sex of the animal can be discerned, e.g. larger animals like pigs, cows and dogs, then male animals are Masculine and female animals are Feminine.

If the biological sex of the animal is difficult to discern on sight, then its Gender is based on the size and shape of the animal. The longer and larger the animal, the more likely it is to be Masculine. The smaller and more spherical the animal, then the more likely it is to be Feminine.

As an insect, the biological sex of a centipede is near impossible for a non-entomologist to discern. Although it is small, it appears that the unambiguously long shape of the insect places it in the Masculine category.

- Locative

C – 7 ta nela bou yotuan = It will go boom over there

yotuan is built from three components:

The second component is the Distal Suffix –ua, which indicates a great distance away.

The third component is the Masculine Suffix –n.

There are three Distance Suffixes which can be added to the Demonstrative yot-.

The Proximal is –a, the Mid-Distal is –u, and the Distal is –ua.

At a glance, it looks as though the lattermost suffix is built from the former two put together. The process whereby this has occurred is unknown to me at this time. Is it a coincidence, did the two team up to build the third, or did the latter break down?

- Temporal

C – 8 hem miemki yota = I am going ahead now

Relevant to the socio-linguistic situation of Yeri is the fact that all Yeri speakers wield some degree of fluently in Tok Pisin, an Englis-based creole language that serves as the lingua franca facilitating communication between the many language groups of Papua New Guinea.

As a result, it is not uncommon for Yeri speakers to use the Tok Pisin word nau to mean now.

yota, meanwhile, is considered the closest Yeri equivalent.

Another example of Demonstratives being used in temporal a meaning is:

C – 9 hello yotui kɨ meiwerewa = in the year that I have already mentioned

psia war is built from three components:

- psia is a word which means arrive, and it only ever occurs alongside the verb ar.

- w- is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Subject Prefix.

- ar is a verb which means to go.

Taken together, psia ar is a compound verb which means to arrive, to reach a location or to come out.

wamena is built from three components:

- w- is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Subject Prefix.

- ana is a verb which means to come.

- -me- is the Imperfective Infix.

As a general rule, only a trained herpetologist can discern the biological sex of most reptiles, including snakes. As a result, the Grammatical Gender of a snake is based on its size and shape.

Like a centipede, a snake is unambiguously long and thin in shape, which implies that it should be Masculine.

However, in contrast to the languages of Western Europe, Grammatical Gender is a somewhat more fluid affair in Yeri. In practice, this means that you can use the less intuitive Gender in order to emphasise a certain characteristic of a particular noun.

In this sentence, the designation of Feminine Gender to harkanogɨl, or snake, indicates that it is very small.

wgamera is built from three components:

- w- is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Subject Prefix.

- gara is a verb which means to dig.

- -me- is the Imperfective Infix.

I would have assumed that wgamera would carry the Object Suffix –wan, but I assume that in the context wherein it appears, it is not strictly necessary.

ndodi is built from two components:

- n- is the 3rd Person Singular Masculine Subject Prefix.

- dodi is a verb which means to stand or to wait.

The complete phrase luten ndodi means something along the lines of the sore which stands.

Having pondered it further, I feel that lute has acquired the Masculine Suffix in order to imply that the open wound is particularly large, thus explaining how the snake was able to enter.

wde is built from three components:

- w- is the Relational Prefix.

- -Ø is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Possessed Object Suffix.

- -de is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Possessor Suffix.

Taken altogether, the phrase luten ndodi hagɨl wde means the sore which stands on her back.

wnobiada is built from four components:

- w- is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Subject Prefix.

- nobia is a verb which means to talk or to speak.

- -da is the 3rd Person Augmented Object Suffix.

- -Ø is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Object Suffix.

haraharahi is an Invariable noun which means friend, and it can refer to men and women alike.

ye is the 2nd Person Singular Pronoun.

In order to create the 2nd Person Plural Pronoun, one simply adds the rare Plural Suffix –m. thus creating yem.

ko is an alternate form of the particle kua, which means still, yet or first, depending on context.

nɨtren is built of four components:

- n- is the 2nd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- ɨtr is the Irrealis form of the verb atr, which means to see.

- -e is the 3rd Person Augmented Object Suffix.

- -n is the 3rd Person Singular Masculine Object Suffix.

What, I hear you ask, is the Irrealis?

Up until this point, all our verbs have been in their Realis forms. Basically, the Realis is used for positive statements of fact.

The Irrealis has a number of uses. In this sentence, the Irrealis carries an Imperative function.

In practice, this means that nɨtren is a command which means you look at him!

maŋan is built from two components:

- maŋa is an Interrogative (or Question Word) which, depending on context, means who, which or what.

- -n is the Singular Masculine Suffix.

maŋa has two different plural forms, depending on whether one is asking about more than one human or more than one inanimate.

The Inanimate Plural is the regular maŋai while the Human Plural is magɨl.

nbanokɨl is built from three components:

- n- is the 3rd Person Singular Masculine Subject Prefix.

- b- is the 1st Person Singular Object Prefix.

- anokɨl is a Realis verb which means to bite.

Yeri contains three Object Prefixes. These are:

The 1st Person Singular Object Prefix b-.

The 1st Person Plural Object Prefix w-.

The 2nd Person Object Prefix y-. (In this respect, it acts in a similar manner to the English 2nd Person.)

wnobia is built from two components:

- w- is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Subject Prefix.

- nobia is a verb which means to speak or to talk.

hiro, which can also take the alternate form hirua, is a particle which expresses negation in general.

ya is a particle whose meaning, at least in linguistic terms, remains unclear.

hiro ya is a relatively common phrase which means not at all.

lolewa, meanwhile, is an Invariate noun which refers to any number of unspecified things.

miakual is the Plural form of miakua, which means frog.

nadɨ is a word which, depending on context, can mean either only or very.

wnamenia is built from three components:

- w- is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Subject Prefix.

- nania is a verb which means to go into or to go inside.

- -me- is the Imperfective Infix.

lutei is the plural form of lute.

I am unsure as to why it is in the Plural and not the Singular.

worme is built from three components:

- w- is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Subject Prefix.

- or is a Realis verb which means to lie down.

- -me is the Imperfective Infix, but because the verb has only a single syllable it becomes a Suffix.

mani is a noun that refers to the inside of something.

yawi is a noun which means tail. Its plural form is yawigal.

wden is built from three components:

- w- is the Relational Prefix.

- -Ø is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Possessed Item Suffix.

- -den is the 3rd Person Singular Masculine Possessor Suffix.

For some reason, when a Genitive Pronoun contains a 3rd Person Possessor, whether it be Plural or Singular, it can only take the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Possessed Item Suffix.

In practice, regardless as to the Gender of the Possessed Item, only wde and wden are the valid forms of her and his respectively.

The forms *wnde and *wnden are invalid.

wnobiada is built from four components:

- w- is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Subject Prefix.

- nobia is a verb which means to talk or to say.

- -da is one of several Yeri Augmented Object Suffixes.

- -Ø is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Object Suffix.

harkanogɨl is the Singular form of the noun harkanogɨ, which means snake.

nanor is built from two components:

- n- is the 3rd Person Singular Masculine Subject Prefix.

- anor is a verb which means to descend.

In the previous sentence, the snake took Feminine Gender, whereas in this one, it takes Masculine Gender. This is an interesting example illustrating how Gender Assignment in Yeri is somewhat of a more fluid affair compared to Western Europe.

Here, we can imagine that the speaker chose to assign the snake as Masculine in order to elicit the image of a snake wriggling its long thin body into the woman’s sore.

norme is built from three components:

- n- is the 3rd Person Singular Masculine Subject Prefix.

- or is a verb which means to lie down.

- -me is the Imperfective Suffix, which becomes an Infix following the 1st syllable in longer words.

hamual is a singular noun which means belly or stomach. The plural form is hamualgɨl.

As you may have noticed, it does not take any Locative Suffixes or Prefixes. Indeed, as far as most nouns are concerned, the Locative is implied via context, and is not explicitly stated.

wye is built from three components:

- w- is the Relational Prefix.

- -Ø is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Possessed Item Suffix.

- -ye is the 2nd Person Singular Pronoun Suffix.

The 3rd Person Pronouns are the only ones that take a slightly different form when present in a Genitive Pronoun, i.e. the initial /t/ undergoes lenition and becomes a /d/. (In layman’s terms, it softens.)

mɨlmkialen is built from five components:

- m- is the 1st Person Singular Subject Prefix

- ɨlkial is the Irrealis form of the verb alkual, which means to pull.

- -m- is the Imperfective Infix.

- -e is the 3rd Person Augmented Object Suffix.

- -n is the 3rd Person Singular Masculine Object Suffix.

Here we see another purpose of the Yeri Irrealis, which is to indicate a Negative Sentence.

In Yeri, all negated verbs take the Irrealis Mood.

When it appears between two consonants, the Imperfective Infix –me- is abbreviated to –m-.

This also show us that, as far as Yeri is concerned, the syllable break occurs between the /l/ and the /k/. Some might have assumed that it came between the /k/ and the following vowel, but that does not appear to be the case.

In this sentence, aro is an alternate form of the verb ar, which means to go (and which appears shortly where it is preceded by the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix Ø-).

I mention this because the verb aro actually means to carry by resting the strap of a container across the forehead.

tɨnogɨl is a noun which can mean village or villages.

amo is built from two components:

- Ø- is the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- amo is the irregular Imperfective Conjugation of the verb o, which means to be.

As mentioned earlier, the noun wul refers to any form of water.

wo is built from two components:

- w- is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Subject Prefix.

- o is a verb which means to be.

The adjective weli can mean either to be hot in temperature or the often related meaning of to be painful.

Taken altogether, the phrase amo wul wo weli means they made the water hot.

However, the literal meaning of amo wul wo weli is somewhere along the lines of they are, the water is hot.

ameyaka is built from five components:

- Ø- is the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- aya is a verb which means to give to someone.

- -me- is the Imperfective Infix.

- -ka is the 3rd Person Augmented Object Suffix.

- -Ø is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Object Suffix.

The verb aya can also mean to plant something. When it is used in this context, it takes the 3rd Person Feminine and Masculine Object Infixes –he- and –ne- respectively.

woheka is built from three components:

- w- is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Subject Prefix.

- oka is a Realis verb which means to drink.

- -he- is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Object Infix.

oka has an irregular Irrealis in the form of okɨ. (It is irregular since it is typically the 1st vowel in a Realis verb that will change in order to create the Irrealis.)

I mention this because okɨ also functions as a Realis verb, where it means to use, and furthermore takes the regular Irrealis form iekɨ.

wormia is built from two components:

- w- is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Subject Prefix.

- ormia is the irregular Imperfective form of the verb o, which means to be located at.

As you may have noticed from this and other sentences, Yeri does not use any equivalent to the word and in order to separate verbs.

Only nouns can be separated with an equivalent to and, and this is done via the verb ode.

goimabɨ is built from three components:

- gobɨ is an alternate form of the Realis verb goba, which means to bend in half.

- -i- is the 3rd Person Plural Object Infix.

- -ma- is another form of the Imperfective Infix.

When an Object and an Imperfective Infix occur within the same verb, the Object comes first.

Thus, if replace the 3rd Person Plural Object Infix with the Singular Feminine or Masculine equivalents, you get gohemabɨ and gonemabɨ respectively.

lapaki is the singular form of the noun meaning tongs. Wilson specifies that this refers to “a piece of bamboo, cane or other material that has been bent in half to permit [the] moving of hot items.”

lapaki can take three related plural forms, these being lapakigal, lapakihegal and lapakilgal, though I do not know whether there are conventions governing when they are used.

olbɨl is built from two components:

- Ø- is the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- olbɨl is an intransitive verb which means to enter.

yo is a verb that has three meanings, these being i) a path or a road; ii) a door, and; iii) an opening or a hole.

In context, these can be distinguished based on their different plural forms.

For path or road, the plural form is yo lapi; for door, the plural is yobaliagi; and for opening or hole, the plural remains yo.

nobia is built from two components:

- Ø- is the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- nobia is a verb which means to speak or to talk.

nobia ta, which literally means they will speak, here means they want.

This is because the verb nobia can also mean to want, when it is followed by another verb.

amotɨwa is built from four components:

- Ø- is the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- amotɨ is the irregular Imperfective conjugation of the realis verb otɨ, which means to hold something.

- -wa is the 3rd Person Augmented Object Suffix.

- -Ø is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Object Suffix.

harkanogɨl, which is the singular form of the noun harkanogɨ, means snake. In direct contrast to the languages of Western Europe, it takes in a single sentence both Feminine and Masculine Gender simultaneously.

almkialen is built from five components:

- Ø- is the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- alkial is a verb which means to pull.

- -m- is the Imperfective Infix.

- -e is the 3rd Person Augmented Object Suffix.

- -n is the 3rd Person Singular Masculine Object Suffix.

hiro, which is a general Negation word, here means but, no. As far as I am aware, Yeri lacks a specific word meaning but, and that its meaning is derived from context.

noimo is built from three components:

- n- is the 3rd Person Singular Masculine Subject Prefix.

- omo is an irregular form of the verb oga, which means to eat.

- -i- is the 3rd Person Plural Object Infix.

omo is used instead of oga when it occurs in a sentence containing predicate morphemes.

ni is an Invariate noun which means intestines, and it also appears in the expression ni nɨbuegi, which means food.

weide is built from three components:

- w- is the Relational Prefix.

- -ei is the 3rd Person Plural Possessed Item Suffix.

- -de is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Possessor Suffix.

I am not entirely sure as to why noimo appears twice in this sentence. Perhaps this is to indicate that due to their length, the intestines took a long time to eat.

nonemo is built from three components:

- n- is the 3rd Person Singular Masculine Subject Prefix.

- omo is a verb which means to eat.

- -ne- is the 3rd Person Singular Masculine Object Suffix.

wan is an Invariate noun which means heart, and based on the previous verb, it appears to take Masculine Gender Agreement.

wde is built from three components:

- w- is the Relational Prefix.

- -Ø is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Possessed Item Suffix.

- -de is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Possessor Suffix.

As mentioned earlier, if the Genitive Pronoun contains a 3rd Person Possessor and a 3rd Person Singular Possessed Item, the latter always takes Feminine Gender Agreement, even if the Possessed Item is Masculine.

In context, this means that the seemingly correct *wan wnde is not allowed.

hamote is a noun which means individual, and yuta is an adjective which means female.

When placed next to one another, we get the form hamote yuta, which means woman or that woman.

walmo is built from two components:

- w- is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Subject Prefix.

- almo is an intransitive verb which means to die.

In case you were wondering, almo takes the regular Imperfective Infix –me-, which gives us the form almemo.

wodɨ is built from two components:

- w- is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Subject Prefix.

- odɨ is an alternate form of the verb ode, which means to be with, though it often takes the translation and.

I assume that odɨ is the form taken by ode when it is not followed by an Object Suffix.

In this instance, the lack of an Object Suffix could be in order to create cross-verbal agreement with walmo, which never takes an Object Suffix.

ode is built from three components:

- Ø- is the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- ode is a verb which means to be with.

- -Ø is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Object Suffix.

Here, ode combines with the following verb ormia to create ode ormia, which roughly translates as they sit with her, even though a more literal translation would be they are with her, they sit.

aro and ormia are both built from two components, the first in each case being the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix Ø-.

ormia is the irregular Imperfective form of the verb o, which means to stay; aro is an alternate form of the verb ar, which means to go.

gamerade is built from five components:

- Ø- is the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- gara is a verb which means to dig, although in this instance it means to bury.

- -me- is the Imperfective Infix.

- -de is the 3rd Person Augmented Object Suffix.

- -Ø is the 3rd Person Singular Feminine Object Suffix.

The verb gara takes on of two Augmented Object Suffixes. When a human is being buried, it takes the Augment Suffix –de; when anything else is being dug or buried, the Augment Suffix –wa is used.

aro is built from two components:

- Ø- is the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- aro is an alternate form of the verb ar, which means to go.

As far as I can discern, the short phrase aro yotu hepa has a rough literal meaning of they go – that is all.

yotu is built from three components:

- yot is the Yeri Base Demonstrative.

- -u is the Middle Distance Suffix.

- -Ø is the Singular Feminine Suffix.

For a more in-depth discussion of the Yeri Demonstratives, I refer you to the analysis under Sentence 11.

hepa is built from two components:

- he is a the Continuous Particle.

- -pa is the Additive Suffix.

In Yeri, the Continuous Particle has a number of functions.

First, it indicates that the action or event is still ongoing, as the name suggests.

In addition, it also implies a permissive attitude towards the event or action, e.g. “let it happen” or “it is okay if it happens”.

However, further research is required to understand the Particle’s full range and complexity.

The Additive Suffix, meanwhile, has a wide range of meanings, most of whose translations lie somewhere along the lines of also, too or still. It takes a number of forms depending on where it occurs, but they all starts with either /p/ or /b/, followed by a single vowel.

pɨrsakai is a Singular Noun which means story, although the connotation is typically legend, and it can take the alternate form sɨprakai, this being formed via Metathesis (the process whereby two sounds, typically consonants, swap places.)

The plural form is pɨrsakaigɨl or sɨprakaigɨl.

tiawa is the Singular Feminine form of the adjective tiawa, which simply means short.

laladɨl is an Adjectival Intensifier which means very. It only occurs alongside two adjectives, these being tiawa, which means short, and sɨpekɨ, which means to be little or small in size or amount.

nadɨ is also another Adjectival Intensifier that also means very, but it can occur alongside any adjective.

antjeriñ is built from two components:

- an- is the Body Part Classifier.

- -tjeriñ is a Suffix which means one.

In Warray, there are numbers from 1 to 5, and they are all built from a number of components.

The numbers are:

1 – antjeriñ; 2 – keraŋlul; 3 – keraŋantjeriñ; 4 – yelikeraŋlul; and 5 – annepattjeriñ.

We will explore the components later, but for now you should be able to discern some patterns.

altumaru is built from two components:

- al- is the Human Female Classifier Prefix.

- tumaru is a noun which means old woman.

Although it is referred to as the Human Female Classifier Prefix, al- also occurs on nouns that refer to humans without inherent or explicit gender. (Although it is worth noting that not all human nouns require a Noun Classifier Prefix.)

yuŋuyiñ is the irregular Imperfective Conjugation of the verb yaŋ, which means to go, to walk or to fly.

There is no explicit Subject Prefix, which means that the action is being carried out by a single man or woman.

Here is the full Conjugation Paradigm for yaŋ:

Imperative: yaŋ

Realis: yatjiñ

Irrealis: yiñ

Imperfective: yuŋuyiñ

puk:aniñ is the regular Imperfective Conjugation of the verb puk:aŋi, which means to hunt.

Here is the full Conjugation Paradigm for puk:aŋi:

Imperative: puk:aŋ

Realis: puk:aŋi

Irrealis: puk:an

Imperfective: puk:aniñ

In general, the Imperfective is used to indicate a habitual or recurring action.

Because both yuŋuyiñ and puk:aniñ are in the Imperfective, the two activities are inherently related.

tjatpulayi is the Ergative Case Declension of the noun tjatpula, which means old man.

In Warray, the Ergative Case marker is only used in order to clear up potential ambiguity. In most contexts, it is optional.

(For whatever reason, tjatpula does not take the Human Male Classifier Prefix a-. This is true for a surprisingly high number of nouns referring to human males.)

kuntiyiniñ is the regular Imperfective Conjugation of the verb kuntiyiñ, which means to smile, to laugh or to play, with it being possible for the last to indicate inappropriate sexual behaviour.

Here is the full Conjugation Table for kuntiyiñ:

Imperative: kuntiyi

Realis: kuntiyiñ

Irrealis: kuntiyin

Imperfective: kuntiyiniñ

anwak is an Adjective which means little or small.

mamam is a noun which means both daughter and son. Warray does not have individual words that refer exclusively to one or the other.

akalawu is the Dative Case Declension of the pronoun akala, which means he.

Unlike most languages discussed thus far, Warray actually makes a grammatical distinction between he and she.

Also in Warray, the Dative Case takes on a Genitive function, and thus akalawu can mean his or to him.

katjiyaŋ is built from two components:

- katji is the Non-Proximate Demonstrative Pronoun.

- -yaŋ is the Origin Suffix.

katji is a direct equivalent to the English word that, e.g.

C – 10 ŋiri katji kawawamal = That dog is barking

(Strangely enough, there is no Warray Proximate Demonstrative Pronoun, i.e. an equivalent to the English word this.)

As its name suggests, the Origin Suffix indicates that something functions as a source or cause of something. It can also indicate movement away from an object or location.

By itself, katjiyaŋ is a Conjunction which, depending on context, translates into English as then, therefore, because of (this), thus and so.

Here, altumaru has received the translation of woman. This is to avoid repetition of the word old.

In order to refer to a woman in general, the Warray word is alkulpe, while the term for Warray woman is alwaray.

Last, but not least, we have pulmiñ, which is the regular Realis Conjugation of pulmal, which means to be angry or to become angry.

Here is the full Conjugation Paradigm for pulmal:

Imperative: pulma

Realis: pulmiñ

Irrealis: pulmal

Imperfective: pulmalañ

Non-Complete Potential: pulmi

Warray has no fewer than 8 regular Verb Conjugation Paradigms. For most of these Paradigms, the Imperfective and Non-Complete Potential are identical.

In this sentence, altumaru does not take the Ergative Case Suffix because the context makes it unnecessary.

pokliliñ is the irregular Imperfective Conjugation of the verb poklam, which means to make a string by rubbing the fibres of the banyon tree on one’s thighs.

Here is the full Conjugation Paradigm for poklam:

Imperative: pokli

Realis: poklam

Irrealis: poklen

Imperfective: pokliliñ

puñi means banyon tree. In his grammar, Harvey identifies it as the species Ficus virens.

As well as meaning rope and Milky Way, anpik can also refer to a string or a fence.

pulam is the Realis Conjugation of the regular verb pulam, which means to make or to cure.

Here is the Conjugation Paradigm for pulam:

Imperative: pula

Realis: pulam

Irrealis: pulan

Imperfective: pulaniñ

In this sentence, we have an Imperfective and a Realis verb. In this situation, the implication is that the Imperfective verb is done in order to achieve the Realis one, e.g. the banyon is rubbed on the thigh in order to make a rope.

tjatpula means old man.

yatjiñ is the Realis Conjugation of the irregular verb yaŋ, which means to go.

Now, you may be wondering how Warray distinguishes between Past, Present and Future Tense.

This is done via the choice of Subject Prefix.

In Warray, Subject Prefixes fall into one of three categories: Complete, Non-Complete and Potential.

Here, we need only concern ourselves with the first two.

yaŋ is an Active Verb, which means that it operates under a Past/Non-Past Distinction.

The 3rd Person Singular Complete Subject Prefix is Ø-, giving us:

C – 11 akala yatjiñ = he went

C – 12 alkala yatjiñ = she went

Meanwhile, the 3rd Person Singular Non-Complete Subject Prefix is pa-, giving us:

C – 13 akala payatjiñ = he goes or he will go

C – 14 alkala payatjiñ = she goes or she will go

puk:aŋi is the Realis Conjugation of the regular verb puk:aŋi, which means to hunt.

tjipak:u is the Dative Declension of the noun tjipak, which refers to fish in general.

In his grammar, Mark Harvey includes the names of 18 specific fish and 2 unidentified species. That said, only a few of them include the Latin names, which are:

tumtingtingu = Glossogobius giurus

tuntun = Glossamia aprion

mun = Ophieleotris aporos and Oxyeleotris lieolatus

kalalpa = Nematolosa erebi

wayiñ is the Realis Conjugation of the regular verb wayiñ, which means to return, both in the sense of to go back as well as to come back.

Here is the full Conjugation Paradigm for wayiñ:

Imperative: wayi

Realis: wayiñ

Irrealis: wayin

Imperfective: wayiniñ

ñiliñ is the Realis Conjugation of the regular verb ñilal, which means either to bring or to bring up.

Here is the full Conjugation Paradigm for ñilal:

Imperative: ñila

Realis: ñiliñ

Irrealis: ñilal

Imperfective: ñilalañ

Non-Complete Potential: ñili

Last, but not least, we have tjipak, which means fish.

The prior appearance of tjipak:u confirms that it is the man who hunted and brought the fish, rather than te other way round.

punwuy is built from two components:

- pun- is the 3rd Person Plural Object Prefix.

- wuy is the Realis Conjugation of the regular verb wuy, which means to give.

Here is the full Conjugation Paradigm for wuy:

Imperative: wu

Realis: wuy

Irrealis: wun

Imperfective: wuniñ

As mentioned previously, mamam means son/daughter while akalawu means to him/of him or his.

keraŋlul is the Warray word for two. Its construction is explored below.

wuyi is the Realis Conjugation of the irregular verb wuyi, which means to hang or to climb.

Here is the full Conjugation Paradigm for wuyi:

Imperative: wuy

Realis: wuyi

Irrealis: wuñ

Imperfective: wuniñ

In this sentence, anpik takes on the meaning of rope.

natlakiñ is built from two components:

- nat- is the Unexpected Object Prefix.

- lakiñ is the Realis Conjugation of the irregular verb lakil, which has many meanings.

The Unexpected Object Prefix is used to clarify something that could be unclear. In this context, it indicates that the rope is the thing that was dropped, since the woman is not specifically mentioned.

The full range of meanings for lakil is to chuck, to toss, to push, to drop, to throw without aiming and to put somewhere without a location in mind.

Here is the full Conjugation Paradigm for lakil:

Imperative: laki

Realis: lakiñ

Irrealis: lakil

Imperfective: lakilañ

yañ is the Imperative Conjugation of the highly irregular verb tjim, which means to come, to arrive or to approach.

Here is the full Conjugation Paradigm for tjim:

Imperative: yañ

Realis: tjim

Irrealis: tjimin

Imperfective: tjiminiñ

altumaruyi is the Ergative Case Declension of the noun altumaru, which means old woman. The Ergative Case specifies that it is the woman who is doing the talking, although here it is clear from the presence akalawu, which specifies that it is the man who is being told something.

tjiyi is the Realis Conjugation of the irregular verb tjiyi, which means: to say, to do, to call, to promise, to mean and to believe.

Here is the full Conjugation Paradigm for tjiyi:

Imperative: tji

Realis: tjiyi

Irrealis: tjiñ

Imperfective: tjuŋutjiñ

You’re probably wondering why I chose to use the irregular form clumb as oppose to the far more common form climbed.

Well, a few months ago I read Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain, and I came to have an aesthetic preference for the one over the other. Indeed, even though I spent the first 23 years of my life ignorant to the existence of clumb, I have come round to the perspective that climbed looks more irregular.

Personally, I preferred Tom Sawyer, which I read just before. I’ve never been able to warm to phonetic spelling, and the more fantastical plot of Huck didn’t quite strike the right tone following Tom’s more down-to-earth subject matter.

I should, however, admit that my favourite scene in both was the boys‘ attempts to rescue the slave Jim in Huck Finn. I shan’t spoil it for those who wish to discover it for themselves.

mi is the Realis Conjugation of the highly irregular verb mi, which means to get, to grab or to pick up.

Here is the full Conjugation Paradigm for mi:

Imperative: may

Realis: mi

Irrealis: mañ

Imperfective: mayim

milwikyi is the Instrumental Declension of the noun milwik, which here means mussel shell.

The Instrumental Case, as suggested by the name, indicates the tool or instrument with which an action was achieved.

Warray has two words that translate into English as mussel. While Harvey implies that they are separate species, it is not explicitly stated, nor any Latin names given.

tukpu is merely defined as mussel species, while milwik specifies a mussel whose home is in fresh water.

tañmi is the Realis Conjugation of the verb tañmi, which means to cut. It follows the same pattern as the previous verb mi, observe:

Imperative: tañmay

Realis: tañmi

Irrealis: tañmañ

Imperfective: tañmayim

liñ is the Realis Conjugation of the highly irregular verb liñ, which means to fall.

Here is the full Conjugation Paradigm for liñ:

Imperative: liñitañ

Realis: liñ

Irrealis: liŋan

Imperfective: liŋaniñ

In case you were wondering, tjatpula is a fully independent word.

Accordingly, the general word for man is nal, and the word for a Warray man in particular is awaray.

Harvey does not include a specific word for old in his dictionary, nor one for young. Whether this is due to an absence of such words, or because they were victims to the loss of vocabulary among the last speakers, is unclear.

altumaruyi is built from three components:

- al- is the Female Human Classifier Prefix.

- tumaru is a noun which means old woman.

- -yi is the Ergative Case Suffix.

milwikyi, meanwhile, is built from two components:

- milwik is a noun which means mussel or mussel shell.

- -yi is the Instrumental Case Suffix.

As its name suggests, the Instrumental Case Suffix indicates the tool with which an action was carried out.

In languages where the Ergative Case is present, it is not uncommon for it to perform double duty as another Case, typically either the Instrumental or the Locative.

amukuy is a common Warray Exclamation which means okay or enough.

I wonder whether this comes from the English phrase “I’m okay”.

Warray has a number of other Exclamations. Here they all are:

amala = no

kalkal = slow down or wait

katjak:u = true

kuttjari = good thing

lukluk = hurry up

matjpatji = shut up

mulkiŋla = poor fellow or poor thing

yak:ay = heh

yu = yes

yuyu = leave it

At this point, we are about to go through the exact same story again. As a result, I shall try to avoid repeating myself, and thereby provide deeper and wider exploration into the language.

Earlier we mentioned that numbers in Warray are built from a number of components. These are the components in their isolated forms:

- an-: the Body Part Classifier Prefix.

- -tjeriñ, which means one.

- keraŋ, which means two.

- -lul: the Pair Suffix.

- yeli-, a Prefix that appears only once throughout the entire language.

- nepat, a noun which means hand.

In Warray, all 5 numbers are built from a combination of these constituents, even the numbers for one and two. A couple of them go further and enjoy a literal translation.

Here is the exact breakdown:

1: antjeriñ = an- + tjeriñ

2: keraŋlul = keraŋ + -lul

3: keraŋantjeriñ = keraŋ + an + tjeriñ (lit. two-one)

4: yelikeraŋlul = yeli + keraŋ + lul

5: annepattjeriñ = an + nepat + tjeriñ (lit. one hand)

waŋu is the Dative Case Declension of waŋ, which means game, meat or animal.

The Dative Case, in contrast to the other cases present in Warray, has three different forms, these being:

-yu this occurs after the /i/ final verb forms of the –ŋi, -mi and –Ø conjugations, but only when it is not preceded by a palatal consonant, i.e. /tj/, /tj:/, /ñ/ and /y/.

-wu this occurs after all other vowel final stems, as well as on pum.

-u this occurs on all other consonant final stems (or words).

In total, Harvey ascribes 8 functions to the Warray Dative. In this sentence, waŋu exhibits the Purposive function, as can be seen in this example sentence:

C – 15 waŋu ipuk:aŋi kakiŋ = We hunted for meat yesterday

In this sentence, waŋu indicates that the search for meat is the purpose of the hunt.

lam is the Realis Conjugation of the irregular verb lam, which means to spear, to pierce, to shoot or to scratch.

Here is the full Conjugation Paradigm for lam:

Imperative: li

Realis: lam

Irrealis: len

Imperfective: leniñ

pikiriŋu is the Dative Case Declension of the 3rd Person Non-Singular Pronoun pikiriŋ.

In this context, pikiriŋu takes on the Benefactive function of the Dative Case, i.e. the person on whose behalf the action is carried out.

Here is another example of the Benefactive in action, once again involving meat:

C – 16 waŋ patjiyi kapañilal yapuru = They promised to bring some meat for us

yapuru is the irregular Dative Case Declension of the 1st Person Plural Inclusive Pronoun yepe.

In context, yapuru specifies that the person being addressed will also receive some of the meat.

luramiñ is the Realis Conjugation of the regular verb luramal, which means to bring back.

Here is the full Conjugation Paradigm for luramal:

Imperative: lurama

Realis: luramiñ

Irrealis: luramal

Imperfective: luramalañ

Non-Complete Potential: lurami

leriklik is the irregular Allative Case Declension of the noun le, which means camp, country or nest.

The Allative Case, whereof the regular Suffix is –lik, indicates motion towards something.

Like other cases in Warray, the Allative Case Marker can occur on verbs as well as nouns, observe:

C – 17 paliyatjiñ keŋanawu kirilik tjatpula kaninilik = We are going to that hill over there where the old man sits. (In context, this refers to a dreaming site.)

In this sentence, the Allative Suffix appears twice:

- kirilik = kiri + lik = to the hill

- kaninilik = kanini + lik = where he sits

In the latter it acts as the Locative, and creates a link between the two.

alkalawu is built from three components:

- al- is the Human Female Classifier Prefix.

- kala is the 3rd Person Singular Pronoun, though it cannot occur by itself.

- -wu is the Dative Case Suffix.

Warray, unlike many other Australian languages, makes a distinction between Masculine and Feminine in its 3rd Person Singular Pronouns. In simpler terms, it possesses a he/she distinction.

Both these pronouns are built with the dummy pronoun kala. I call it a “dummy pronoun” because it never occurs alone, it must always be preceded by either a- or al-, creating akala (Eng. he) or alkala (Eng. she) respectively.

paniniñ is built from two components:

- pa- is the 3rd Person Non-Singular Complete Subject Prefix.

- niniñ is the Imperfective Conjugation of the Irregular Verb ni, which means to sit, to stay or to squat.

In Warray, verbs take Subject and Object Prefixes in order to indicate who is doing what to whom.

Subject Prefixes divide into three categories: the Complete, the Non-Complete and the Potential.

Here are the Complete Subject Prefixes:

1st Person Singular: at- atniniñ = I was sitting

1st Person Dual Inclusive: ma- maniniñ = Us two, you and I, were sitting

1st Person Plural: i- ininiñ = We were sitting

2nd Person Singular: an- anniniñ = You were sitting (alone)

2nd Person Non-Singular: a- aniniñ = All of you were sitting

3rd Person Singular: – niniñ = She was sitting or he was sitting

3rd Person Non Singular: pa- paniniñ = They were sitting

If you wish to learn more about the Warray Subject Prefixes, all of them are explored in the chapter dedicated to Warray.

antjeriñwuy is built from two components:

- antjeriñ is the Warray word for one.

- -wuy is a Suffix which is glossed in the text as one of.

As much as I tried, I could not find an explanation for the Suffix –wuy.

What I can tell you is that it can also occur by itself as a verb meaning to give.

Here is the full Conjugation Paradigm for wuy:

Imperative: wu

Realis: wuy

Irrealis: wun

Imperfective: wuniñ

Curiously, wuy is a completely regular verb in Warray.

pakuntiyiniñ is built from two components:

- pa- is the 3rd Person Non-Singular Complete Subject Prefix.

- kuntiyiniñ is the Realis Conjugation of the regular verb kuntiyiniñ, which means to smile, to laugh or to play.

almutek is the Human Female form of the adjective mutek, which means big.

If we add to this the Inchoative Suffix –nayiñ, we get the verb almuteknayiñ, which means either to become female human big, or more succinctly to become pregnant. For example:

C – 17 almuteknayiñ atjaŋki anwak kakankan = She has become female big. Maybe she will have the baby (soon) or She is pregnant. Maybe she will have the baby (soon).

Consequently, almuteknayiñ cannot be used to refer to a human male.

Instead, one uses amuteknayiñ, which means to become human male big or to become a man. For example:

C – 18 amuteknayiñ nalwiru kayiñyiñ lam = He has become an adult, he is a proper man, his beard has pierced through.

As far as I can tell, the Inchoative Suffix behaves like a regular –ñ Class Verb.

Here is the full Conjugation Paradigm for –nayiñ:

Imperative: -nayi

Realis: -nayiñ

Irrealis: -nayin

Imperfective: -nayiniñ

Warray, in fact, has two Inchoative Suffixes, one for Adjectives and one for Nouns.–nayiñ is used for nouns (though this category behaves differently than in English, as seen in the examples above.)

punnay is built from two components:

- pun- is the 3rd Person Plural Object Prefix.

- nay is the Realis Conjugation of the regular verb nay, which means to see or to look.

Warray has a total of 7 Object Prefixes, and these are:

1st Person Singular: pan- pannay = She saw me

2nd Person Singular: ana- ananay = She saw you

3rd Person Singular: – nay = She saw him

1st Person Plural: in- innay = She saw us

2nd Person Plural: in- innay = She saw all of you

3rd Person Plural: pun- punnay = She saw them

In addition, the 3rd Person Plural Object Prefix has the variant put-, which only occurs with a 1st Person Singular Subject Prefix.

All of the 1st Person Singular Subject Prefixes also end in /t/, observe:

Complete: at- atputnay = I saw them

Non-Complete: pat- atpatnay = I see them or I will see them

Potential: kat- amala atkatnay = I do not see them or I will not see them or I did not see them

In addition, when it is followed by put-, the Subject Prefix at- is typically omitted, but this is not obligatory.

As well as having both Subject and Object Prefixes, Warray also has a number of Portmanteau Prefixes, i.e. prefixes which combine both subject and prefix.

All the Portmanteau Prefixes include a 1st Person Subject and a 2nd Person Object. We will list them all now.

1st Person Singular Subject > 2nd Person Singular Object:

Complete: ariñ- ariñnay = I saw you

Non-Complete: pariñ- pariñnay = I see you

Potential: kariñ- amala kariñnay = I did not see you

1st Person Singular Subject > 2nd Person Plural Object:

Complete: aritj- aritjnay = I saw all of you

Non-Complete: paritj- paritjnay = I will see all of you

Potential karitj- amala karitjnay = I do not see all of you

1st Person Plural Subject > 2nd Person Object

Complete: ini- ininay = We saw you or We saw all of you

Non-Complete: panini- panininay = We see you or We will see all of you

Potential: kanini- amala kanininay = We will not see you

Before we move on, it is worth mentioning that Subject and Object Prefixes follow this pattern:

- 1st Person Subject

- 2nd and 3rd Person Potential Subject

- Object

- 2nd and 3rd Person Non-Potential Subject

Of course, the category of 1st Person Subject also includes the aforementioned Portmanteau Suffixes. I referred it to a “pattern” as opposed to an “order” because, ultimately, a verb can only take a single Subject Suffix.

neŋkiñ is defined as a Hesitation Form.

Harvey gives it the translation of whatchamacallit, but I prefer my form because it cultivates a sense that the speaker is addressing the listener.

In addition to this, Warray possesses a number of Particles or Prefixes which indicate Attitudes, Knowledge and Predictions. I shall list a few examples here.

- kul-

This indicates that the sentence or clause represents the speaker’s opinion. Examples include: