Today, we shall be exploring a number of the similarities and differences present between two languages with similar names, namely the Jarawa language of India and the Jarawara language of Brazil. Before we can get to this, however, our two languages must first introduce themselves.

Jarawa, also spelt Järawa or Jarwa, boasts approximately 260 speakers scattered across a number of the Andaman Islands, which belong to the nation of India, though geographically they lie far closer to the nation of Myanmar. The name Jarawa does not exist in the language itself. Rather, it means foreigner in the language of the Aka-Bea, the Jarawa’s main nemesis.

The Jarawa refer to themselves as əng, which simply means people.

This language is one of two members of the Ongan family, which occupy the Jarawa and Onge islands that comprise the main bulk of the Andaman Islands.

(If you wish to learn about the demographic make-up of the Andaman Islands, I would highly recommend that you watch the YouTube video that is included in the source list.)

Jarawara, meanwhile, enjoys a nudge over 1,000 speakers in the western part of Amazonas State in Brazil, hidden deep within the Amazon jungle. It has three distinct dialects, all of which are mutually intelligible with each other, although their speakers refer to them as separate languages in order to differentiate the separate tribes which speak them.

Jarawara is a member of the Arawan language family, which consists of around a half dozen members scattered throughout the western edge of the Amazon jungle, with a few creeping over the border into Peru.

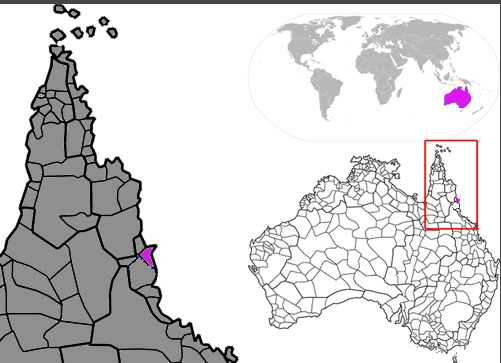

(The location of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. The Andaman Islands, where Jarawa can be found, are those visible within the red rectangle, whereas the Nicobar Islands are simply too small to be visible at this scale.)

Sentence 1:

In order to ease ourselves into this comparison, we will start with a very simple sentence.

English: I am eating

Jarawa: mi tita

Jarawara: otafa oke

At first, the Jarawa language looks very simple, and in truth it is.

The first word, mi, is the 1st Person Pronoun, and it does not change depending on number. Thus, it means both I and we.

In fact, Jarawa has the simplest pronoun paradigm I have ever seen, with only three pronouns, though there are few potential variations of the 2nd and 3rd Person.

tita, meanwhile, is composed of two parts. The first, t-, is a variant of -ɖi, which sometimes denotes either Referentiality, which refers to an event within sight of the speaker &/or hearer, or Definiteness, which refers to a non-visual object whose reference is derived from preceding context.

ita, meanwhile, is simply the root for the verb to eat.

The Jarawara sentence, meanwhile, works quite differently to its Jarawa counterpart, with one notable similarity.

Both words begin with the Prefix o-, which indicates the 1st Person Singular. In both of the words above, it acts as a Conjugation marker, though it possesses other functions.

The first word otafa, is built from the above explained prefix and -tafa, which is the root for the verb meaning to eat.

The second component of the second word is -ke, also known as the Feminine Declarative Suffix, whose purpose is to indicate that the action described is a statement of fact.

The Masculine equivalent, -ka, also serves a number of other purposes, which we shall explore below. As a Declarative Suffix, however, it is only used when the subject of the sentence is referred to as a man in the 3rd person, whether this comes in the form of a male name or 3rd person pronoun.

Thus, for the above statement, it does not matter whether the speaker is a man or a woman.

(The approximate location of the Jarawara peoples and their languages. The state of Amazonas is the largest in the country, and is larger than the combined area of Uruguay, Paraguay and Chile.)

Section 2:

In this section, we will explore several different meanings for the Jarawara Affix ka, which appears as both a suffix and a prefix.

English: My brother-in-law is coming

Jarawa: mawela allema

Jarawara: owabori kakeka

First, we will discuss the Jarawa sentence, which is the simpler of the two grammatically.

mawela means my brother-in-law, referring specifically to the brother of the speaker’s wife, and is comprised of the noun awela and the 1st Possessive Pronoun ma or mi, but because this is an Inalienably Possessed Noun, it is prefixed to the noun.

In Jarawa, most body parts and kinship terms are Inalienably Possessed. Put simply, this means that they are inseparable from the humans who possess them. Thus, if you did not whose brother-in-law was on the way, you would be obliged to use the term wawela, which means his/her brother-in-law.

allema, meanwhile, simply means come, though depending on context it can also mean came.

The Jarawara sentence, meanwhile, begins much the same as the Jarawa, with the word owabori, which means brother-in-law, though it can also refer to someone’s male cross-cousin (i.e. the son of either your mother’s brother or father’s sister).

The first part, o- is the 1st Person Singular Prefix to which we gave considerable attention in the previous section. When attached to a noun, it acts as a Possessive.

kakeka is comprised of three components.

First, we begin with the Applicative Prefix ka-, which has a number of effects. In this context it refers to something being in motion.

Our second component is the Suffix -ke, which refers to motion towards the place where the speaker is located. Depending on a number of phonological (sound) rules, however, it can also take the form -ki, though we will not discuss these rules here. (To add to that, there are a number of further variations which encode additional information)

Last, but not least, we have the Masculine Declarative Suffix -ka, which is used to convey that this sentence is a statement of fact.

(Within the Andaman archipelago lies North Sentinel Island, whose inhabitants are notoriously hostile to outsiders. Based on information collected via satellite, it is possible that following the tribe may have recently initiated its iron age following the washing ashore of a containment tanker.)

Section 3:

In the first two sentences, we focused on the Present Tense, which resulted in sentences that seemed to have a greater number of similarities than differences.

In this section, we will discuss the Future Tense, and how this manifests quite differently between these two enigmatic languages.

English: I will cut down the tree tomorrow

Jarawa: kahiunen mi tang odehehə

Jarawara: awa kaa onaminahabanake

The word kahiunen means tomorrow, though like in German, the same word can also mean morning, or in the morning.

The second word mi, is the 1st Person Pronoun which we discussed earlier, and can also mean we.

The third word tang, means tree. Like English, Jarawa nouns have both singular and plural forms. To build a plural, you add the Suffix -le, which gives us tangle. However, Plural Marking is not obligatory, and the above sentence could easily refer to more than one tree.

odehehə, meanwhile, is built from odehe, which is the verb stem meaning to cut, and the Hypothetical Mood Suffix -hə.

The Hypothetical Mood is used to indicate that it is doubtful whether or not the action described will occur, or a past event whose authenticity is in question. Both of these shades of meaning are indicated via the Suffix -hə.

Aside from a Word Order which tends to place the Object before the Verb, the Jarawara sentence is built very differently.

The word awa is the generic word for tree, and is a Feminine Noun. As expected for a language located deep within a rainforest, there are a number of words for specific species of tree.

(On a side tangent, the words ama and atari have several related meanings which refer to both humans and trees. ama means blood, menstruation and tree sap; while the word atari means skin, fish scales and tree bark.)

Secondly, we have kaa, which is the Infinitive of the Verb for to chop, and it does not conjugate, i.e. it remains forever unchanged.

onaminahabanake, meanwhile, is indeed the monster of a word that it appears to be. Naturally, we will slice this word into sections and examine each in turn.

To start, I will briefly mention the first and last segments, these being o- and -ke, which are the 1st Person Singular Prefix and the Feminine Declarative Marker respectively.

This leaves us with the middle -naminahabana-, which is a magic middle, in the sense that it can be divided by three.

Immediately following the 15th letter of the Latin Alphabet is the Applicative Suffix -na. This is a necessary addition to a sentence whose main verb does not conjugate.

Or in plainer English, you can think of it as meaning something like do or make. Thus, if you put kaa and -na(-) together, you get something akin to do the chopping or make the chopping, though hopefully not as clunky.

Following on we meet the suffix -mina, which means tomorrow.

In contrast to English and Jarawa, the Jarawara language has no individual words for tomorrow, today, yesterday and a number of other time markers. These all manifest themselves as Verbal Suffixes.

Our final suffix, -habana, is the Feminine Future Suffix. (The masculine equivalent is the confusingly similar -hibana.)

(The Purus river, along which the Jarawara live. On the whole they are a sedentary people who derive most of their livelihood through hunting, gathering and fishing.)

Section 4:

In this section, we explore another significant difference between these two languages. Namely, that the latter has a separate mood for Reported Speech, while the former does not.

English: The pig is reported to have eaten a banana

Jarawa: hi atyiba hwəwə čonel ita

Jarawara: boroko jifari tafahimonaha

This time around, we will begin by analysing the Jarawara sentence.

We start with the word boroko, which is a variation of the Portuguese word porco, which means pig, and is a Masculine Noun.

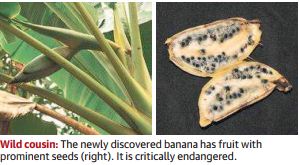

Preceding this we have jifari, which means banana.

tafahimonaha is composed of two moving parts. The first part, which we have seen before, is tafa, which means to eat.

The second part, himonaha, is the Masculine Reported Speech Suffix. This means that the speaker has, at best, second-hand evidence that the event described took place. The Feminine equivalent of this is hamonehe, though with this being said, they each have a number of reduced variants depending on other grammatical factors.

Reported Speech does not exist as a separate mood in English. Instead, you use a construct along the lines of is said to have or is supposed to have.

Now we move to the Jarawa sentence.

Our first clause is the simple phrase hi atyiba, which is formed from hi, which is the 3rd person pronoun, and atyiba, which means say or said.

Word for word it means s/he said, though one could instead it is said, which sounds more natural in this context.

hwəwə means pig, while čonel means banana.

ita, meanwhile, is formed from ita, which means either eat or ate.

Taken altogether, the Jarawa sentence translates roughly as: it is said, (that) the pig ate the banana.

(In 2017, a new species of wild banana was found within the dense jungle of the Andaman Islands. It has been named Musa paramjitiana in honour of Paramjit Singh, the director of the Botanical Survey of India.)

In conclusion, I hope that this has been an interesting comparison between two languages who are little heard of even within their own home countries, let alone outside of them.

I would also like to mention that there is another language known as Jarawa, which is spoken in Nigeria. I was unable to find any grammatical resources for this language, so for the time being there won’t be a comparison between two languages with the exact same (English) name.

This has no doubt left many people heartbroken.

Our next exploration will take us north to Alaska, where we will discuss the Eyak language of Prince William Sound. Until then,

Same Wilf-time!

Same Wilf-channel!

Sources:

Pramod Kumar, Descriptive and Typological Study of Jarawa (New Delhi: Jawaharlal Nehru University 2012)

R. M. W. Dixon, The Jarawara Language of Southern Amazonia (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2004)

Google Images

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andaman_Islands

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mad%C3%AD_language

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arawan_languages

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amazonas_(Brazilian_state)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jarawa_language_(Andaman_Islands)