Unua is an Austronesian language, falling within the Central-Eastern Oceanic subgroup. Beyond this, it falls into the Vanuatu group of languages, whereafter its exact genetic classification becomes confused and contested.

In any case, it is not considered a Polynesian language, in case I make that mistake later (and did not remove it in time).

As of 2011, the current population of Unua speakers was approximately 1,000, though other sources give quite different results.

That said, despite its low speaker number, the language may have a strong future, as it remains the language that most Unua speakers use in every day interactions. Though it should be noted that some parents will try and speak to their children in Bislama, an English-based Creole language, in the belief that knowledge of the language will help them later in life.

With members of other communities, Bislama is the principal language used. Church services are often held in Bislama, as many pastors are from outside the area.

Malekula is the second-largest island in the archipelago of Vanuatu, and it is located in the North of the territory. Unua shares the island with around 20 other languages from the same over-arching family. It is most closely related to the Pangkumu language, from whose speakers it is separated by just one river.

Although Unua is spoken on the Eastern coast of the island, the Unua speakers gain most of their sustenance from the land, and relatively little from the sea.

I even found a few blog posts from people who visited Malekula. They all said that Malekula has very few tourists. I ask you to keep it this way.

I would never seek to inflict a tourism industry on even my worst enemies. Of course, if you want to visit Malekula, take zero selfies, and stay at least a month to really get to know the people, then you have my blessings.

With that out of the way, let’s go!

- I am here again, Elder Kalangis.

- I want to tell a story.

- This story goes like this.

- There was a small island and there were people living on it, and the people used to choose a chief from among them.

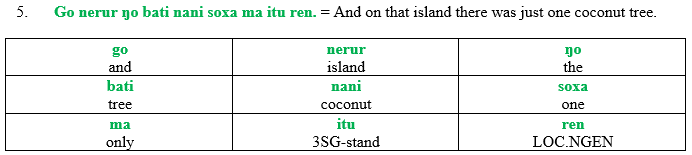

- And on that island there was just one coconut tree.

- And the chief was wanting to eat one of the coconuts, but he couldn’t.

- This was because people were going early in the morning and taking the fruit of the coconut.

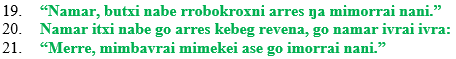

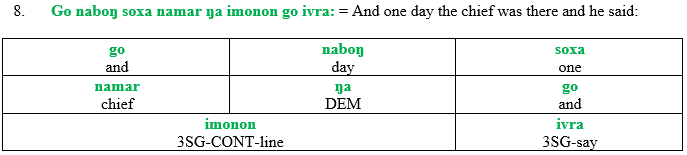

- And one day the chief was there and he said:

- “Oh, I know what I can do.

- I will now make a law so that people will not take the fruit of the coconut.”

- The chief beat the drum and all the people came, and the chief said, he said:

- “I will now make a law that any person that picks a fruit of the coconut, then the person that has picked a coconut will pay the penalty of one pig.

- This law will hols for three months, if coconuts fall down then I will again beat the drum and everybody can come and I will share out the common fruit with everybody.”

- And the people said:

- “O, chief very good, OK we will start today.”

- So it went on until the three months were up, and they did not see any coconut fruit fall from the tree.

- This was because the chief went every day and picked the coconut fruit and ate them.

- The people came and said the chief, they said:

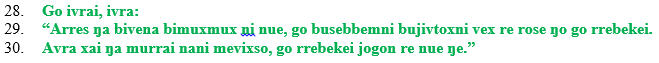

- “Chief, beat the drum for us to find the person who is eating the coconut.”

- The chief beat the drum and all the people came, and the chief said, he said:

- “OK, you say that you can find who it is who is eating the coconut.”

- And a boy said:

- “Chief, I know how to find him.”

- And the chief said:

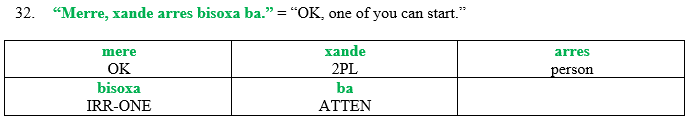

- “Okay, you do it.”

- The boy went off and he cut off a cane of bamboo and he filled it with water and he cut off a laplap leaf.

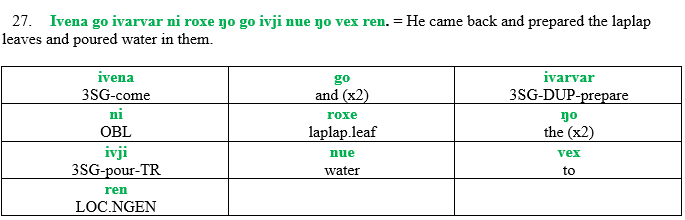

- He came back and prepared the laplap leaves and poured water in them.

- And he said, he said:

- “Each person should come up and sip some water, but you should not drink it, you should pour it out on the laplap leaf and we will see.

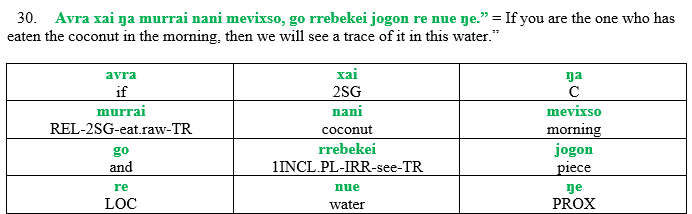

- If you are the one who has eaten the coconut in the morning, then we will see a trace of it in this water.”

- The chief said:

- “OK, one of you can start.”

- And the people said:

- “No, chief, you go first, because you made the law.”

- Then the chief went and sipped the water and spat it into the laplap leaf, and they saw there a piece of coconut.

- The people walked away one by one

- Now they no longer believed in their chief.

- They got together and they got another chief to look after them.

- This story ends here.

Before I analyse the language, I shall analyse the story.

First, it is curious to note that after the discovery of the chief’s dishonesty, they do not commit violence on his person. Instead, they simply leave him.

Consider where the Polynesians and their history. They are an island-hopping people, whose feet are as stable on a sea-bourne raft as they are on the ground. Maybe he stayed on the island, heavily chastened, or maybe he sailed for another land. There are plenty of not-yet inhabited islands in the South Pacific.

Is the fate of the chief a factor that the Malekulan story teller would not need to explain, because his listener would know it as he knows the fingers on his hand, or the knots in his raft?

Secondly, it does not state whether the chief paid the penalty of one pig. Of course, the original penalty would have been paid to the chief, so will he pay it to the new chief?

In addition, this tells us that pigs were amongst the animals that the Polynesians brought to Malekula. Indeed, Malekuka is one of the largest islands in the archipelago of Vanuatu, so we can assume that all four animals – Pigs, Rats, Dogs and Chickens – are represented amongst the settlers of that island.

Kalangis Bembe, also known as Elder Kalangis, is the Chief of Ruxbo village, which housed around 90 speakers of Unua (circa 1999).

He contributed 19 of the 47 oral recordings with which Pearce constructed her grammar.

He is also responsible for most of the modern work in Unua. As of 2014, he had translated all 4 Gospels and part of Acts, as well as 154 hymns. Extracts from the Gospels appear all throughout this article.

Whilst I could not locate the Gospels directly, I did find a document containing more stories in the language, though I’m not sure if you can access them without signing in. A link is included in the Source List.

The Chief of the Island

xina is the 1st Person Singular Pronoun.

In Unua, all Pronouns take Singular, Dual and Plural forms, and in the 1st Person, there is a further distinction between Inclusive and Exclusive, but we will discuss those later.

For now, here is an example of the Singular:

11 – 1 Baxa vex Lakatoro bovri mere xina. = I will go to Lakatoro to buy my bed.

baxa is built from three components:

- b- = the Irrealis Prefix.

- a- = the 1st Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- -xa = a Verb which means go.

vex is a Preposition which means to.

Lakatoro is a town in Central-North Vanuatu.

bovri is built from four components:

- b- = the Irrealis Prefix.

- o- = the 1st Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- vr = a Verb which means buy.

- -i = the Transitive Suffix.

By itself, bovri means something like, I will buy it.

mere is a Noun which means bed.

mere xina is an example of Direct Possession, although the alternative merog is equally acceptable. Both of these mean my bed.

For an example of Indirect Possession, the respective forms are mererr se xina and mererr sog respectively.

At this point, I do not understand the Unua distinction between these two forms of possession. If Pearce explains it in her grammar, I am currently yet to find it.

In this section, we will discuss the Unua Cardinal Numerals. We will start with the numbers from 1 to 10:

- soxa 6. morovtes

- xeru 7. morovru / merovru

- xeter 8. morovtor / merovtor

- xevej 9. moropej

- xerim 10. saŋavur

In the numbers 2-5, the initial consonant xe-, which is similar to the root morpheme for “stick/tree”. This is a common feature across the many languages of Vanuatu.

The numbers 11-19 are formed as through the formula: 10 rromon X”. Thus:

- saŋavur rromon soxa 16. saŋavur rromon morovtes

- saŋavur rromon xeru 17. saŋavur rromon morovru

- saŋavur rromon xeter 18. saŋavur rromon morovtor

- saŋavur rromon xevej 19. saŋavur rromon moropej

- saŋavur rromon xerim

In order to form the numbers from 20-90, ŋavur (a shortened form of saŋavur) is followed by the multiplicand. What is a multiplicand? The following list should give you enough context:

- ŋavur xeru 60. ŋavur morovtes

- ŋavur xeter 70. ŋavur morovru

- ŋavur xevej 80. ŋavur morovtur

- ŋavur xerim 90. ŋavur moropej

In order to create numbers such as 21-29, 31-39, 41-49 etc.…, one uses the same pattern as used in 11-19. For example:

- ŋavur xeru rromon xeru 66. ŋavur morovtes rromon morovtes

- ŋavur xeter rromon xeter 77. ŋavur morovru rromon morovru

- ŋavur xevej rromon xevej 88. ŋavur morovtor rromon morovtor

- ŋavur xerim rromon xerim 99. ŋavur moropej rromon moropej

I will end this section here. Unua does have higher numbers, but these have a number of eccentricities which would take a while to explain. I may return to them in a later section, if there is nothing else to discuss.

Unfortunately, many younger speakers struggle with the Unua number system. The Numbers 3-9 confuse them, whilst control over numbers higher than 10 eludes them.

This is because they have, to varying extents depending on speaker, been replaced by their equivalents in Bislama, an English-based creole that is one of the national languages of Vanuatu, and is used as a lingua franca between speakers of different native languages.

As you will see as we continue, Unua places its numbers after the thing being counted.

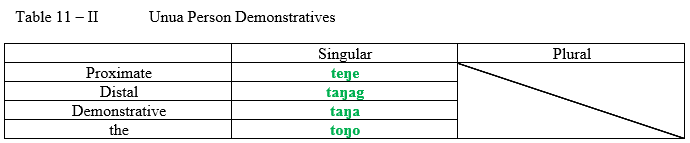

Unua has a very large repertoire of Demonstrative Modifiers, a number of which we will feature in this narrative. Since our example sentences will involve a contrast of these, I shall include the whole table here:

Before we dissect our example sentences, I shall quickly lay out two curiosities in this table:

- The Plural forms are formed through the Infix –ar-.

I mention this because Infixes are incredibly rare amongst world languages.

- The Demonstrative and the forms can both function as Previous Mention markers, which we may explore later.

For now, here our two example sentences, which should demonstrate the difference between the Proximate and Distal Modifies, as well as indicate their English Equivalents:

11 – 2 Robburet ŋe iperrperr, robburet ŋag imetmet. = This book is red, that book is black.

11 – 3 Robburet ŋare reperrperr, robburet ŋarag remetmet. = These books are red, those books are black.

As you may be able to figure out, robburet is a Noun which means book.

ŋe is the Non-Plural Proximate Demonstrative Marker, and ŋag is the Non-Plural Distal Demonstrative Marker. They can be receive the English translations this and that, based on the following context:

iperrperr is built from two components:

- i- = the 3rd Person Singular Realis Subject Prefix.

- perrperr = an Adjective which means red.

imetmet is built also from two components:

- i- = same as the above

- metmet = an Adjective which means black.

ŋag is the Plural Proximate Demonstrative Marker, and ŋarag is the Plural Distal Demonstrative Marker. They can be directly translated into English as these and those respectively.

reperrperr is built from two components:

- re- = the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- perrperr = red.

remetmet is built also from two components:

- re- = same as above.

- metmet = black.

The Subject Prefixes are a topic that will arise during the rest of the article. Appreciators of certain Australian languages will be sorely disappointed to hear that Unua makes provision only for Subject Prefixes.

You will see zero Object or Portmanteau Suffixes here.

Unua has a few Genitive particles, some of which we will discuss later. Here, we will begin with the base form se.

- naxat se motara = the man’s basket

- naxat se Sande = Sande’s basket

As you can see, the possessed thing goes before se, and the possessor goes after. This is also true for pronouns, for example:

- naxat se rrarru = our basket

- naxat se memru = our basket

Both of these Pronouns are Dual, which means that they each refer to exactly two people. The difference is that the first is Inclusive, i.e. it belongs to me, the writer, and you, the reader; while the second is Exclusive, i.e. it belongs to me, the writer, and a person who is one of my friends (or another one of my friends, depending on whether you’re chill or not).

With the Non-Singular Pronouns, this is the pattern. With the Singular Pronouns, on the other hand, one has two strategies:

- naxat se xina / naxat sog = my basket

- naxat se xai / naxat som = your basket (or thy basket)

- naxat se xini / naxat sen = his/her basket

According to Pearce, there is no semantic difference between the two strategies. The meaning does not change depending on which you use, although I imagine that the stress and nuance might be different.

Earlier I mentioned that Unua has a distinction between Direct and Indirect Possession. The Genitive se is an example of the Indirect.

In this section, we will briefly explore the 3rd Person Singular.

As seen above, the 3rd Person Singular Pronoun is xini, which can translate as he, she or it, depending on context.

(As I have said before, and will no doubt say again: the he/she distinction is not only a minority feature amongst all 6,000 of the world’s languages, it is also an innovation.)

The 3rd Person Singular has one Prefix, this being i-. For example:

11 – 4 Ikeke muxni nebo ŋe. = She sang this song.

ikeke is built from two components:

- i- = the 3rd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- keke = a Verb which means sing.

Unua is a heavily Pro-Drop Language, which means that you do not need to say the pronouns.

muxni is built from two components:

- mu = a Particle which means again.

- -xni = the Oblique Case Suffix.

nebo is a Noun which means song, and ŋe is the Proximate Demonstrative Modifier.

As we will explore later, the Subject Prefixes make a distinction between Singular and Non-Singular. The former make a distinction between Realis and the other forms, whilst the latter do not. This is further reflected in how the prefixes interact with one another.

In this section, we will explore the Continuous Mood, which indicates either an ongoing or a habitual event, as well as something generic. It appears as the Prefix mo-.

Outside of context, any event marked with the Continuous can take place in the Past, Present or Future. For example:

11 – 5 Rate romomajiŋ re naman. = They are working in the garden. / They were working in the garden.

romomajiŋ is built from three components:

- ro- = the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- mo- = the Continuous Mood Prefix.

- majiŋ = a Verb which means work.

rate is the 3rd Person Plural Pronoun.

re is the Locative Preposition, an all-purpose equivalent to English in, at, on, etc.…

naman is a Noun which means garden.

In Unua, the distinction between Past, and Present Tense can be ambiguous. Based on Pearce’s list of abbreviations, there do not appear to be any Suffixes, Prefixes or other Affixes that specify the time when an event took place.

The General Transitive Marker –i indicates that the verb acts upon an object (or patient). For example:

11 – 6 Tusebxani rre naix se mende. = You cannot eat our fish.

tusebxani is built from five components:

- t- = the Definitive Future Tense Prefix

- u- = the 2nd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- seb- = the Negative Prefix.

- xan = a Verb which means eat.

- -i = the Transitive Suffix.

rre is a Negative Particle, which means not.

naix is a Noun which means fish; se is the Genitive Marker; and mende is the 1st Person Plural Exclusive Pronoun.

Thus, naix se mende refers to a fish that belongs to us, but not to you, the reader.

Now, it is worth pointing out that many Transitive verbs have 2 alternate forms: one with the Suffix –i, and one without.

The Verb eat is one such example, bearing the forms xani and xenxen.

Here is an example featuring the latter:

11 – 7 Xai ujajar xini buxenxen go busebmajiŋ rre? = Do you want to eat without working?

buxenxen is built from three components:

- b- = the Irrealis Prefix.

- u- = the 2nd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- xenxen = a Verb which means eat.

Pearce speculates that when the Verb is not suffixed, the “interpretive focus” revolves around the activity, as oppose to the object that it concerns.

This makes a lot of sense. In the examples that Pearce herself gives, the suffixed form is always followed by the thing being eaten (or specifically not), whereas with the un-suffixed form, food is rarely mentioned.

She also gives other examples where this heuristic holds true.

In many previous articles, I have largely left Phonology aside in favour of grammar. This is partly due to lack of interest, a result whereof was that I did not know enough thereabout to comment.

In this section, I shall quickly cover how a few of the sounds present in the above sentence are pronounced.

/x/ is the easiest to explain. It appears to function like /x/ in most dialects of Spanish, i.e. an English /h/.

/ŋ/ is just like the /ng/ in words like sing or song.

/b/ is the most difficult to explain, because it looks just like the English equivalent. It is a pre-nasalised consonant, which means that it is pronounced more like /mb/, though you don’t pronounce the /m/ as a separate consonant.

Think of it like the /mb/ in comb, but you pronounce the /b/ without changing how the /m/ is pronounced.

I may take another dive into Unua’s phonology and orthography later in the article, but we will see.

ju is a Post-Verbal Aspect Particle which indicates either Perfective or Imperfective Aspect. This means that almost every sentence with ju is translated into the Past Tense, with the above being an exception.

For example:

11 – 8 Go vin ŋo ikei ŋa irriraŋ bitab ju. = And the woman saw that she would not be able to remain hidden.

The above is a segment of the Gospel of Luke, Chapter 8, Verse 47. The whole Verse runs thus: And when the woman saw that she was not hid, she came trembling, and falling down before him, she declared unto him before all the people for what cause she had touched him, and how she was healed immediately. (King James Version).

go is a Connective which means and, and we will explore it briefly later in this section.

vin is a Noun which means woman, and ŋo functions as a Definite Article.

ikei is built from three components:

- i- = the 3rd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- ke = a Verb which means see.

- -i = the Transitive Suffix.

ŋa is a Complementiser Particle, which we may explore later.

irriraŋ is built from two components:

- i- = the 3rd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- rriraŋ = a Verb which means not able.

bitab is built from three components:

- b- = the Irrealis Prefix.

- i- = the 3rd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- tab = a Verb which means hide.

In addition to appearing by itself, ju can combine with go (meaning and), to create goj, which is typically followed by nu, which means now.

goj nu literally means something like already now, but how does this work in practice?

11 – 9 Xini iri naur goj nu. = He is writing a letter now. / He has already written a letter.

As you can tell, the translation of goj nu depends on whether the event takes place in the present or took place in the past. One should think of them as complementing and emphasising one another.

In Unua, the 3rd Person Plural Pronoun is rate, and its accompanying Subject Prefix is rV-, the uppercase /V/ indicating that it duplicates the following vowel.

11 – 10 Go rabvase jiten sobon xise arres rebekei, rabvase daŋaro xise rabagrasi arres se Atua. = And they do some things so that people will see, they do those things to deceive the people of God.

As you can tell, this is another excerpt from scripture. This comes from the 22nd Verse of the 13th Chapter of the Gospel of Mark, and the complete verse goes: For false Christs and false prophets shall rise, and shall shew signs and wonders, to seduce, if it were possible, even the elect. (King James)

Since this is a long sentence, I shall only focus on those verbs containing the aforementioned Subject Prefix rV-, these being:

rabvase, which appears twice, and is built from three components:

- ra- = the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- b- = the Irrealis Prefix.

- vase = a Verb which means make.

rabagrasi, which is built from four components:

- ra- = the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- ba- = the Irrealis Prefix.

- gras = a Verb which means see.

- -i = the Transitive Suffix.

rebekei, which is also built from four components:

- re- = the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- be- = the Irrealis Prefix.

- -ke = a Verb which means lie.

- -i = the Transitive Suffix.

Some of you will have noticed is that the Irrealis Prefix also takes Vowel Harmony. We will explore the Irrealis later.

Unua has a number of quantifiers which, just like the cardinal numbers discussed earlier, come after the noun that they modify. Here, we will discuss kebeg (or tebeg), which means all or every. Since kebeg is the form that appears in this tale, we will explore an example involving the form tebeg:

11 – 11 Nojajarni namar ŋarag tebeg rebvena re xenen. = I hope that all the chiefs will come to the feast.

The phrase namar ŋarag tebeg means all the chiefs, and its three components are thus:

- namar = a Noun which means chief.

- ŋarag = the Plural Distal Demonstrative Modifier.

- tebeg = a Quantifier which means all.

Another translation of this phrase is all those chiefs.

nojajarni is built from three components:

- no- = the 1st Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- jajarn = a Verb which means wish or hope.

- -i = the Transitive Suffix.

rebvena is built from three components:

- re- = the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- b- = the Irrealis Prefix.

- vena = a Verb which means come.

re is the Locative Marker, which here translates as to, and xenen is a Noun which means food, though here a better translation is feast.

In some circumstances, kebeg/tebeg can occur discontinuously from that which it quantifies, for example:

11 – 12 Nojajarni namar ŋarag rebvena tebeg re xenen. = I hope that all the chiefs will come to the feast.

This sentence differs only from the previous in that rebvena and tebeg have switched places. Both these sentences are equally grammatical.

Other quantifiers that function in a similar manner include sobon (some), iŋot (many), meraŋ (many/ a large number of) and navon (nothing).

Another is xevis (a few), which also functions as the Interrogative how many.

In this section, we will finally discuss the Irrealis Prefix, which takes the form of b- or bV-.

This has a very wide range of uses, all of which revolve around indicating an unrealised or hypothetical event. It typically indicates a Future event, for example:

11 – 13 Mevix mevixso rrubsoji bbue. = Tomorrow morning we will go pig hunting.

rrubxoji is built from four components:

- rru- = the 1st Person Dual Inclusive Subject Prefix.

- b- = the Irrealis Prefix.

- xoj = a Verb which means hunt.

- -i = the Transitive Suffix.

mevix is a word which means tomorrow, whilst mevixso is a Noun which means morning.

bbue is a Noun which means pig.

Another use of the Irrealis Prefix is as an Imperative, which is used for giving commands. Unua does not possess a separate Imperative marker. For example:

11 – 14 Buvartoxni bitox. = Leave it where it is.

buvartoxni is built from four components:

- b- = the Irrealis Prefix.

- u- = the 2nd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- vartox = a Verb which means leave.

- -ni = the Oblique Suffix.

By itself, buvartoxni can also mean you will leave it.

bitox is built from three components:

- b- = the Irrealis Prefix.

- i- = the 3rd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- tox = a Verb which means remain.

bitox also has a more literal meaning of it will remain.

As a result, the sentence can also be translated as you will leave it (and) it will remain (there).

The Irrealis Prefix has a lot of uses, and thus we may return to it later.

Unua has many verbs that take partial or fully reduplicated forms. Many verbs seem to have only a reduplicated form. Many reduplicated forms will have slightly different meanings, the more interesting whereof are listed below.

mejmej = lazy (mej = dead)

xejxej = itchy (xej = bite)

bbuŋbbuŋ = roll up (bbuŋ = bend)

ŋavŋav = rest (ŋav = breathless)

tavtav = share out (tav = pour)

saxsax = put out hand (sax = climb)

One thing you may have noticed here is that many of the “verbs” listed above seem more like adjectives. This is because in Unua, Adjectives operate just like Verbs.

Indeed, those few of you who read the tables may have noticed that Numbers also operate like Verbs, i.e. they take the same Prefixes.

In the previous section, I mentioned that Adjectives in Unua function like verbs. In this section, I shall illustrate this principle:

11 – 15 Ei, ivretin go nu toŋo imosuri. = Eh, that is right, he was following him.

ivretin is built from two components:

- i- = the 3rd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- vretin = an Adjective which means true.

Taken by itself, ivretin means something like it is true or that is true.

Another component of this sentence whither I would like to draw your eye is toŋo, which in this context takes the translation he.

More properly speaking, however, it is a Demonstrative Person Modifier.

In addition to the General Demonstrative Markers explored above, Unua also possesses some specific derivations thereof.

I do not know if, in this context, the Singular can also act as a Dual.

Here is another example of one of these demonstratives:

11 – 16 Ale, rumobbunbbunsi vinkiki ŋo temen, runon ixa ixa go toŋo ibo. = Okay, they were watching the girl’s father, and they stayed on until the body stank.

In this context, toŋo translates as the body by itself.

In this section, we will briefly discuss the 1st Person Plural.

Just like the 1st Person Dual briefly discussed above, the 1st Person Plural also makes a distinction between Inclusive and Exclusive:

Inclusive: rrate = all of us (including you, the reader)

Exclusive: mende / memde = all of us (but NOT you)

The Inclusive Prefix is rrV-, whilst the Exclusive Prefix is mVm-, both of which resemble their respective Pronoun.

Here is our example of the Exclusive Prefix:

11 – 17 Mira, mende mamjajar xini jiten se mambxani. = Mother, we would like to have something to eat.

mamjajar is built from two components:

- mam- = the 1st Person Plural Exclusive Subject Prefix.

- jajar = a Verb which means wish.

mambxani is built from four components:

- mam- = the 1st Person Plural Exclusive Subject Prefix.

- b- = the Irrealis Prefix.

- xan = a Verb which means eat.

- -i = the Transitive Suffix.

Now, in this sentence there is no Verb which means to have.

jiten is a Noun which means thing, and se is the Genitive Particle.

Taken altogether, jiten se mambxani means something like the thing of our eating it.

If we give the sentence as a whole a more literal translation, we get something along the lines of Mother, we wish for a thing of our eating it.

Our example of another Inclusive sentence goes:

11 – 18 Ale, rrate rrobosuri ba mama se rrate. = Okay, let’s just go after our mother.

rrobosuri is built from four components:

- rro- = the 1st Person Plural Inclusive Subject Prefix.

- bo- = the Irrealis Prefix.

- sur = a Verb which means follow.

- -i = the Transitive Suffix.

The phrase mama se rrate is built from three components:

- mama = a Noun which means mother or mama.

- se = the Genitive Particle.

- rrate = the 1st Person Plural Inclusive Pronoun.

Taken altogether, this phrase means mother of us, or more succinctly our mother. (Of course, the more poetical mother of ours, is heavily encouraged.)

In addition, this sentence includes the Particle ba, which we will explore much later in this article.

In Unua, the Locative Particle re can translate into many different English equivalents, all of which indicate location. Here are a number of examples, with the equivalent English word underlined:

11 – 19 Ruxenxen re noxobb soxa. = The two of them ate at the same fire.

noxobb is a Noun which means fire.

Though it typically means one, in this sentence soxa receives the translation same.

11 – 20 Ubbrare xina re merog. = You disturbed me in my bed.

merog is a Noun which means my bed, with mero being bed, and –g being the 1st Person Singular Suffix.

11 – 21 Buluk totox soxa iber re natan. = A big cow is lying on the ground.

natan is a Noun which means ground.

11 – 22 Ixoji demej re arres rin. = He casts devils from people.

arres is a Noun which means person, whilst rin is a Plural Marker for those instances when you wish to make it explicit.

11 – 23 Memrej rroni rate re nevar. = We spoke with them through hand signs.

nevar is a Noun which means hand sign.

What does that “C” below ŋa in the table above mean?

The “C” stands for “Complementiser, and it is used to link two clauses. For example:

11 – 24 Niŋe imere ivsexni ŋa reberax xini xande. = This is a sign that they do not want you.

This is another line from Scripture, this being the 11th Verse of the 6th Chapter of the Gospel of Mark. In the King James Version it goes thus: And whosoever shall not receive you, nor hear you, when ye depart thence, shake off the dust under your feet for a testimony against them. Verily I say unto you, It shall be more tolerable for Sodom and Gomorrha in the day of judgment, than for that city.

Now this sentence, can be divided, appropriately enough, into a trinity of units.

By itself, niŋe imere translates to something like this one is like.

ŋa translates directly to that.

Standalone, reberax xini xande means they do not want you.

In our next sentence, the Complementiser ŋa appears twice, and we will analyse it here;

11 – 25 Xande mimbevsexni ŋa xande mimve natin tata ŋa re mamiren. = You will show that you are the children of the Father in Heaven.

This sentence has 5 divisions, these being thus.

xande mimbevsexni means something like you will show it.

Again, ŋa receives the English translation that.

xande mimve natin tata means you are the children of the Father.

A more literal translation of this goes you (all) are His child, the Father.

In its second appearance, ŋa receives the translation of, though in the Lord’s Prayer it would function as that, which or who, depending on the translation.

re mamiren means either in Heaven or in the sky.

This quotation comes from the 45th Verse of the 5th Chapter of the Gospel of Matthew, and it runs: That ye may be the children of your Father which is in heaven: for he maketh his sun to rise on the evil and on the good, and sendeth rain on the just and on the unjust.

The Abbreviation “OBL” is short for “Oblique”, which precedes an Indirect Object. (In other languages this is called the Dative, but the Oblique is typically much broader.)

The Oblique Marker takes three forms, these being: xini, xni and ni.

One example:

11 – 26 Nixe ivrai xini xini: = The tree said to her:

The first xini is the Oblique Marker.

The second xini is the 3rd Person Singular Pronoun.

There does not appear to be any semantic difference between the three forms of the marker. Our next two examples will feature the same verbs as in the above:

11 – 27 Nemen ivrai xni mokiki: = The bird said to the boy:

11 – 28 Ivrai ni mokiki: = He said to the boy:

In all three of the examples above, we have the verb ivrai, which is built from three components:

- i- = the 3rd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- vra = a Verb which means say.

- -i = the Transitive Suffix.

In most instances, the Oblique Marker translates as to. Though in many circumstances, it does not receive any English equivalent.

It would take too long to describe all its uses, but I may return to them later.

The 2nd Person Singular Pronoun is xai, and it takes the Subject Prefix u-.

Here is one example:

11 – 29 Go xai burivsai vin ŋa Elisabet xini ive bitinser se xai soxa. = And you know that the woman Elizabeth is a member of your family.

burivsai is built from four components:

- b- = the Irrealis Prefix.

- u- = the 2nd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- rivsa = a Verb which means know.

- -i = the Transitive Suffix.

xai appears twice in the above sentence.

In the first instance, it directly translates as you, and functions as a Subject Pronoun.

Its second appearance is in the phrase bitinser se xai soxa, which breaks down thus:

- bitinser = a Noun which means family.

- se = the Genitive Marker.

- xai = the 2nd Person Singular Pronoun.

- soxa = the Number one.

More literally, this Noun Phrase translates to one of your family.

This piece of Scripture comes from the 36th Verse of the 1st Chapter of the Gospel of Luke, which goes: And, behold, thy cousin Elizabeth, she hath also conceived a son in her old age: and this is the sixth month with her, who was called barren.

Furthermore, we have the 2nd Person Singular Suffix –m, an example whereof runs:

11 – 30 Butumrax taŋag bivena biravi danom. = You get up, that one will come and take your place.

danom is built from two components:

- dano = a Noun which means place.

- -m = the 2nd Person Singular Suffix.

Taken altogether, danom translates to your place.

Thus goes the 9th Verse of the 14th Chapter of the Gospel of Luke: And he that bade thee and him come and say to thee, Give this man place; and thou begin with shame to take the lowest room.

Earlier, we explored the Unua Quantifier kebeg/tebeg, which means all or every. In this section, we will explore another Quantifier, this one being meraŋ. For example:

11 – 31 Naxerr ŋa Iesu iorej rrobb, meraŋ arres rerexmari iog. = While Jesus was still speaking, a large number of people appeared there.

This is passage comes from Luke 22:47. I shall place the KJV at the end, but in this instance, Pearce provides the Bislama equivalent, this being: Taem Jisas i stap toktok yet, plante man oli kam tru long ples ya.

Now, whilst it may look like a foreign language to the uninitiated, I can see that each word has a direct English equivalent. If you look at it for a while, some of them might jump out at you.

For example, plante is derived from the English word “plenty”.

The phrase meraŋ arres is built from these two components:

- meraŋ = a Quantifier which indicates a group of things.

- arres = a Noun which means person.

In this context, meraŋ translates to a large number of.

Amongst the other Quantifiers, meraŋ is interesting because it occurs before the Noun it modifies, whilst the others occur after.

This phrase takes the Verb rerexmari, which is built from two components:

- re- = the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- rexmari = a Verb which means appear.

Thus, rerexmari means they appear.

The full verse in the King James Bible goes thus: And while he yet spake, behold a multitude, and he that was called Judas, one of the twelve, went before them, and drew near unto Jesus to kiss him.

Unua has a number of Interrogatives, or Question Markers, which all have reasonably direct English equivalents. In this section, we will analyse just one, this being ase, which means who. For example:

11 – 32 Xina nove ase? = Who am I?

xina is the 1st Person Singular Pronoun.

nove is built from two components:

- no- = the 1st Person Singular Realis Subject Prefix.

- ve = a Verb which means be.

Thus, nove is a direct translation to the English am.

ase is an Interrogative which means who.

This sentence puts the Interrogative at the end, instead of the beginning. In general, the Unua Interrogative has much more freedom within the sentence as to where it goes.

Though if you uttered the sentence I am who?, the most you would get is an accusation of being overly poetic.

Again, this is also a piece of Scripture. It comes from the 27th Verse of the 8th Chapter of the Gospel of Mark, and it goes: And Jesus went out, and his disciples, into the towns of Caesarea Philippi: and by the way he asked his disciples, saying unto them, Whom do men say that I am?

In this section, we will continue with our exploration of the Unua Interrogative ase, which means who.

Here is another example thereof:

11 – 33 Go romoravi nevet se rate ji ase? = And who do they give their money to? OR And to whom do they give their money?

The phrase ji ase is built from two components:

- ji = a Particle which indicates Direction.

- ase = the Interrogative who.

Taken together, ji ase translates as either to who or to whom.

Unlike in proper English, there is no Unua equivalent to whom. There is only ase, which can mean who or whom depending on context.

The phrase nevet se rate is built from three components:

- nevet = a Noun which means money.

- se = the Genitive Particle.

- rate = the 3rd Person Plural Pronoun.

Thus, nevet se rate translates to their money or money of them.

romoravi is built from four components:

- ro- = the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- mo– = the Continuous Prefix.

- rav = a Verb which means take.

- -i = the Transitive Prefix.

romoravi roughly translates as they are giving it.

go is a Particle which means and.

This sentence comes from the 25th Verse of the 17th Chapter of the Gospel of Matthew, which goes: He saith, Yes. And when he was come into the house, Jesus prevented him, saying, What thinkest thou, Simon? of whom do the kings of the earth take custom or tribute? of their own children, or of strangers?

This section will continue from the last one. Here, we will briefly mention the verb verrem, an example whereof is:

11 – 34 Ai, xamru murvena murverrem ta? = Ai, what did you two come and do?

murverrem is built from two components:

- mur- = the 2nd Person Dual Subject Prefix.

- verrem = a Verb which means do what?

By itself, murverrem means something like you two do what?.

The Verb verrem is inherently interrogative, and it is always followed by an Intensifying particle.

ta is an Intensifier Particle which means something like exact.

murvena is built from two components:

- mur- = the 2nd Person Dual Subject Prefix.

- vena = a Verb which means come.

Thus, murvena means you two come.

xamru is the 2nd Person Dual Pronoun, i.e. the two of you.

In this section, we discuss another example of the 2nd Person Dual:

11 – 35 Xamru, mursebrex rrobb? = You two, are you not married yet?

mursebrex is built from three components:

- mur- = the 2nd Person Dual Subject Prefix.

- seb- = the Negative Prefix.

- rex = a Verb which means marry.

rrobb is a Particle which has two principal meanings. In a Negative Sentence like the one above, it means yet.

In a Positive Sentence, it typically means still, for example:

11 – 36 Raxa romoxaxa rrobb re niser. = They we still going, walking along the road.

raxa is built from two components:

- ra- = the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- xa = a verb which means go.

romoxaxa is built from three components:

- ro- = the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- mo- = the Continuous Suffix.

- xaxa = a Verb which means walk.

As you can see, the Verb for walk is a reduplication of the Verb for go: xaxa verses xa.

As mentioned earlier, the bare form of the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix is rV–, meaning it takes Vowel Harmony.

Before xa, it becomes ra-, but because xaxa is preceded by the non-Harmonious mo-, it becomes ro-.

re is the Locative Particle, and niser is a Noun which means road.

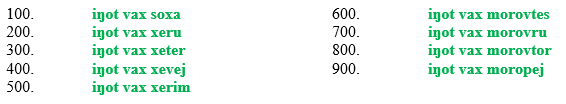

Here, we will take a quick rest from the deep grammar, and return to the Cardinal numbers, which we discussed earlier. In this section, we will explore the numbers from 100 to 1,000.

The pure hundreds are formed from iŋot (which means many), followed by vax (which means times), followed by the multiplicand. Thus, we get:

Now, to build numbers from 101-110, 201-210, etc., one adds rromon to the same pattern as that explored earlier with numbers from 11-19. Thus:

In order to add any number greater than 10 to you hundred, you use ŋavur instead of rromon, which then precedes the unit number. For example:

That was probably one of the most difficult lists I have ever had two write for one of these articles. I mentioned earlier that many younger Unua have difficulty with Unua numbers higher than three, preferring the Bislama equivalents, and I can now understand why.

1,000. iŋotŋot jer vax soxa

iŋotŋot is a partial Duplication of iŋot, which means many.

In other contexts, the word jer means forever.

Thus, this literal translation is possible:

11 – 37 Iŋotŋot jer vax soxa = Many-many forever times one.

We may come back to another use of thousands later in this text, or we may not. We will see.

Earlier, I mentioned that Unua has several Genitive Particles, two of which appear in the above sentence.

For now, we will quickly discuss nen, also known as the N Genitive.

In some contexts, nen can indicate a relationship of Association or shared Space, for example:

11 – 38 rivux nen bbujindes = middle of the water / middle of the sea

11 – 39 rivuz nen naman = middle of the garden

11 – 40 neter nen nani = a rope for a goat

11 – 41 neter nan rrerrŋe = an earring

As you can see, Unua has the same word for ring and rope. Whilst this could be a coincidence, I am inclined to believe that this indicates a number of shared materials and construction techniques.

In addition, nen can also indicate a relationship of Purpose, for example:

11 – 42 naim nen matur = a sleeping house

11 – 43 naim nen taxabbuxen = a cooking house

11 – 44 nabbu nen barbaren = a sword / a fighting knife

11 – 45 nabbu nen nue = a bamboo for carrying water

Of course, there are some usages of nen which do not fall into either of the above categories, for example:

11 – 46 naxerr nen bivan = fruiting season

11 – 47 naxerr nen naus = rainy season

Naturally, these lists do not begin to cover the full gamut of nen’s usage. For example:

11 – 48 Mevix nen ire mokiki ikeke mu. = The next day she heard the boy singing again.

The phrase mevix nen roughly means the next day, with mevix by itself meaning morrow.

Pearce provides a few examples wherein nen translates as next, whilst in others its function is difficult to describe. I shall explore another example thereof below.

Whilst nen gave me some trouble, ren is much simpler. It is simply the combination of nen with the Locative Preposition re. For example:

11 – 49 Ase naim sen xini ixa vex ren? = To whose house did he go?

By itself, the Noun Phrase vex ren translates to the clunky to of it.

The Noun Phrase ase naim sen means whose house, although a more literal translation is who house his/her.

In fact, this is one of the few sentences where I can give a full word-for-word translation. Thus:

11 – 50 Ase naim sen xini ixa vex ren? = Who house his he went to it?

In other contexts, ren translates to something like to it, in/on it or there.

Above, I promised another sentence containing nen. Here it is:

11 – 51 Raru ŋa vemu nen ivra: = The older of the two said.

raru is the 3rd Person Dual Pronoun, i.e. the two of them or they two / the two.

ŋa is the Complementiser.

vemu is a Particle which means before.

Here, nen means something like of them or from them.

Thus, on a literal level, the Noun Phrase has a literal translation something akin to:

11 – 52 Raru ŋa vemu nen. = From the one of those two who is before.

Having broken down this sentence in this way, I am no closer to understanding nen. Indeed, I might be further away. As is typically the case, it is the small words that prove to be the most difficult.

I imagine that nen is one of those words that makes the most sense when one has started to speak the language, and is stumbling with great momentum towards conversational fluency.

In this section, we will discuss the Resultative Suffix –toxni, which indicates the state that flows from previous actions. It is actually built from two components, which are:

- tox = a Verb which means remain or stay.

- ni = the Oblique Particle.

(This etymology apart, Pearce typically gives it the Gloss RSLT-TR.)

Here are a number of verbs that combine with –toxni to create new menaings:

bsitotoxni = smash (bsi = fall on top of)

ritoxni = unscrew (ri = turn)

revtoxni = take off (ravi = take)

kartoxni = take off (kare = put on / wear)

With a few exceptions, the –toxni forms are typically transparent, though often unpredictable, derivations of the bare form.

kare and kartoxni is unusual in that the two forms have semantically opposite meanings. Of course, one can make the argument that taking one’s clothes off is a result of putting them on in the first place. Since we are born naked, the putting them on always comes first.

Another example goes:

11 – 53 Bbue ŋa isusu ixa go isuatoxni batin nixe demen rin. = The pig was pushing away and it butted down huge tree trunks.

isuatoxni is built from three components:

- i- = the 3rd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- sua = a Verb which means head butt.

- -toxni = the Resultative Suffix.

In this context, -toxni translates as the down in butted down.

Curiously enough, the Verb meaning push is su.

Of course, the similarity between su and sua could be a pure coincidence. On the other hand, it could indicate a headstrong people.

Unua also possesses a number of other verbs which perform extra duty as Suffixes. We will look at a few of these later.

In Unua, Conditional clauses are typically introduced via the particle avra, which means if. Alternative forms include avsa and ava.

In most contexts, avra takes Initial Position. Since the following sentence is quite complex, I shall break down the whole thing.

11 – 54 Avra unon ukei nemen namarr soxa isar regeri xai imovsexn xina nomej ju. = If you stay and see a dove flying near you, it is a sign that I am already dead.

avra introduces the Conditional Clause.

unon is built from two components:

- u- = the 2nd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- non = a Verb which means stay.

ukei is built from three components:

- u- = the 2nd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- ke = a Verb which means see.

- -i = the Transitive Suffix.

The Noun Phrase nemen namarr soxa is built from three components:

- nemen = a Noun which means bird.

- namarr = a Noun which means dove.

- soxa = the Number one.

isar is built from two components:

- i- = the 3rd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- sar = a Verb which means fly.

The Phrase regeri xai is built from two components:

- regeri = a Preposition which means near.

- xai = the 2nd Person Singular Pronoun.

If we remove avra, we can create the following independent sentence:

11 – 55 Unon ukei nemen namarr soxa isar regeri xai. = You are staying and you see a dove flying near you.

Curiously, the word for dove (namarr) is very similar to the word for chief (namar), which is likely why the former is always preceded by nemen (bird). Whilst this could be a coincidence, it could also indicate a mythological connection. (Remember that in order to ascertain whether the flood was to recede, Noah sent forth doves.)

Considering the number of Bible verses we have seen so far, combined with the aesthetic of such a maritime people as the Polynesians, such a connection would be highly interesting.

imovsexni is built from four components:

- i- = the 3rd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- mo- = the Continuous Prefix.

- vsexn = a Verb which means show.

- -i = the Transitive Suffix.

xina is the 1st Person Singular Pronoun.

nomej is built from two components:

- no- = the 1st Person Singular Realis Subject Prefix.

- mej = a Verb which means die.

ju is a Particle which means already.

By themselves, these four words create the following standalone sentence:

11 – 56 Imovsexni xina nomej ju. = It shows that I already died.

In some contexts, avra can also follow the main clause. For example:

11 – 57 Nosebnon rre rrarra xai avra usebvena rre navirvir. = I am not waiting for you if you do not come quickly.

On either side of avra we have two sentences which can operate independently of one another. Thus:

11 – 58 Nosebnon rre rrarra xai. = I am not waiting for you.

11 – 59 Usebvena rre navirvir. = You are not coming quickly.

rre is the Negative Particle. Since I spoonfed you the first sentence, I shall allow you to dissect them for yourselves. All the parts are present throughout the rest of the article above.

In the above section, we briefly visited the words namar and namarr, which mean chief and dove respectively. Naturally, you may be wondering what is the difference between /r/ and /rr/?

Without invoking the Latinate Jargon what would confuse you further, /r/ is pronounced as a hard r, whilst /rr/ is, to oversimplify, the rolled r pronounced in many Northern and Scottish dialects of English.

To my knowledge, the difference between /r/ and /rr/ is never phonemic, i.e. it does not distinguish meaning in words. This is not the case in Unua, for example:

naur = colour

naurr = lobster

dere = clam

derre = axe

roni = coconut leaves

rroni = with

I could discuss this further, but after the very long exploration in Section 30, I’ll leave 31 a nice and short one to give you a short respite.

ATTEN is short for Attenuative, and depending on context it translates as perhaps or just, whilst in other cases it acts as more of a Politeness Marker. Here is one example from Scripture:

11 – 60 Namar se rrate ivra bijaŋ ren ba. = Our Master would like to ride it.

Here, I assume that it softens the strength of the sentence.

This sentence has a word-for-word Bislama equivalent, which goes:

11 – 61 Masta blong yumi i wantem yusum fastaem. = Our Master would like to use it.

In this context, the Bislama fastaem is the direct equivalent to the Unua ba.

Another example goes:

11 – 62 E, bukei ba bati xai. = E, just look at your head.

In addition, ba can also take the alternative form ma, for example:

11 – 63 Bukei, baxa ma go begir. = Look, I will just go now and I will come back.

In the above two sentences, ma means translates to just and just now respectively.

In most appearances, however, it does not translate into an equivalent word in English, for example:

11 – 64 Reken ba iberxoxo. = Today it has gotten cold.

reken is a word which means today.

iberxoxo is built from three components:

- i- = the 3rd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- ber- = the Inceptive Prefix.

- xoxo = a Verb which means be cold.

The Inceptive Prefix has two functions. It indicates an event which is either about to take place, or has just taken place. Based on the examples presented in Pearce, it is more typically the latter. In this respect, it functions close to a Past Tense or Immediate Past Tense prefix.

If you really need to specify Plural Number on nouns, you can use the Plural Marker rin. For example:

11 – 65 Xorrin nexej rin sobon. = Some of the ant eggs.

xorrin means egg, and nexej means ant.

rin is the Plural Marker, while sobon is a Quantifier which means some.

rin always comes after the Nouns that it modifies, but not always directly. For example:

11 – 66 Irruŋsi nagor ŋa miprei rin. = He lit the canes that he had collected.

The phrase nagor ŋa miprei rin is built from three components:

- nagor = a Noun which means cane.

- ŋa miprei = a Phrase which means that he collected.

- rin = the Plural Marker.

Pearce provides several examples of this sort of structure, but I will provide only one more:

11 – 67 Novra daŋ nen eten go denxobb nen neben rin. = I mean whatever was there in the ashes from her body.

novra is built from two components:

- no- = the 1st Person Singular Realis Prefix.

- vra = a Verb which means say.

The Noun phrase daŋ nen eten is built from three components:

- daŋ = a Noun which means thing.

- nen = the N-Genitive Particle.

- eten = a Noun which means what.

By itself, daŋ nen eten translates to whatever.

My attempt at a literal translation is something along the lines of thing in what or thing of what.

go is a Particle which means and.

It might be more appropriate to put it in the previous Phrase; this is somewhat of an artificial breakdown.

The Noun Phrase denxobb nen neben rin is built from three components:

- denxobb = a Noun which means ash.

- nen = the N-Genitive Particle.

- neben = a Noun which means his body or her body.

- rin = the Plural Marker

By itself, denxobb nen neben means something like ash in her body or ash of her body.

Curiously enough, the word for fire is xobb.

Here, we will discuss the Verb jxe, which means something like not be, not exist or even, in some cases, disappear.

Here are two example sentences:

11 – 68 Robburet metmet ijxe rapon babarxe. = The black book is not on the table.

11 – 69 Robburet metmet rejxe rapon babarxe. = The black books are not on the table.

rapon is a Preposition which means above, although as the final –n is the 3rd Person Singular Suffix, a more literal translation would be on its above or is its above.

babarxe is simply a Noun which means table.

Otherwise, the only difference between the above two sentences is in the Verb –jxe.

In the first, it takes the 3rd Person Singular Prefix i-, creating ijxe, which means it is not.

In the second, it takes the 3rd Person Plural Prefix re-, creating rejxe, which means they are not.

However, the most common use for ijxe is as the Unua word for no. For example:

11 – 70 “Rekei xai, ji ijxe?” “Ijxe.” = Did they see you, or not?” “No.”

rekei is a Verb which means they see it; xai is the 2nd Person Singular Pronoun; and ji is the word for or.

Meanwhile, ijxe gets translated into both not and no respectively. If you wanted to translate ijxe as it is not in both instances, you would get something along the lines of:

11 – 71 “Rekei xai, ji ijxe?” “Ijxe.” = “(Is it the case that) they saw you, or is it not?” “It is not.”

In addition, there is one sentence where –jxe does receive the translation of disappear. It goes thus:

11 – 72 Xorxor ŋaro tisebejxe rre bixa bijbari mamiren rroni natan rubejxe. = Until Heaven and Earth disappear, these laws will not disappear.

The Noun Phrase xorxor ŋaro is built from the following two components:

- xorxor = a Noun which means law.

- ŋaro = the Plural Definite Article.

tisebejxe is built from four components:

- t- = the Definitive Future Negative Prefix.

- i- = the 3rd Person Singular Prefix.

- sebe- = the Negative Prefix.

- jxe = a Verb which means disappear.

rre is the Negative Particle.

Taken by itself, the Phrase tisebejxe rre means something like it is not going to disappear/exist, and contains a whopping Quadruple Negative.

bixa is built from three components:

- b- = the Irrealis Prefix.

- i- = the 3rd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- xa = a Verb which means go.

bijbari is built from four components:

- b- = the Irrealis Prefix.

- i- = the 3rd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- jbar = a Verb which means reach.

- -i = the Transitive Suffix.

Taken together, the Phrase bixa bijbari means something like if it goes and reaches it, although I think that they are the translation for until.

The Phrase mamiren rroni natan is built from three components:

- mamiren = a Noun which means sky.

- rroni = a Preposition which means with.

- natan = a Noun which means land.

rubejxe is built from three components:

- ru- = the 3rd Person Dual Subject Prefix.

- be- = the Irrealis Prefix.

- -jxe = a Verb which means be not or disappear.

It is worth pointing out that the structure of the Unua Sentence is different to the English equivalent.

If I were forced to give a literal translation of the full sentence, it would be something like:

11 – 73 Xorxor ŋaro tisebejxe rre bixa bijbari mamiren rroni natan rubejxe. = The laws will not disappear until it reaches the point that Heaven and Earth no longer are.

Of course, that could be entirely wrong.

This piece of Scripture comes from the 18th Verse of the 5th Chapter of the Gospel of Matthew. The full Verse runs thus: For verily I say unto you, Till heaven and earth pass, one jot or one tittle shall in no wise pass from the law, until all be fulfilled.

Earlier we discussed Compound Verbs built with tox, meaning remain or stay. Here, we will discuss another example:

11 – 74 Irraŋ bivrrarrbbuni noxobb. = He was not able to put out the fire.

irraŋ is built from two components:

- i- = the 3rd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- rraŋ = a Verb which means not able to.

noxobb is a Noun which means fire.

bivrrarrbbuni is built from five components:

- b- = the Irrealis Prefix.

- i- = the 3rd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- vrrarr = a Verb which means kill.

- bbun = a Verb which means kill or be dead.

- -i = the Transitive Suffix.

Thus, a literal translation of the sentence is something like:

11 – 75 Irraŋ bivrrarrbbuni noxobb. = He was not able to kill dead the fire.

In cases when they appear together, vrrarrbbuni tends to be translated as kill dead.

In addition, when it appears in a bbuni compound, vrrarr can undergo a Vowel change. Thus:

11 – 76 Ale, rebevrrerrbbuni. = Okay, they were about to kill him dead.

In other cases, bbuni occurs as a Prefixless verb proceeding the Prefixed vrrarr, for example:

11 – 77 Veveroŋon memvena se mambavrrarri bbuni motara. = Now we come to kill the old man dead.

In such cases, I imagine that bbun be dead acts as an intensifier to vrrarr kill; it emphasises the final end-state of the action.

Another Verb which indicates a Resultative End State is xotvi, which means break.

In contrast to bbuni, xotvi never occurs by itself. One example:

11 – 78 Nabbu itevxotvi sernixen. = The knife cut off his neck.

nabbu is a Noun which means knife¸ and sernixen is a Noun which means his neck, with the bare stem sernixe meaning neck.

itexvotvi is built from four components:

- i- = the 3rd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- tev = a Verb which means cut.

- xotv = a Verb which means break.

- -i = the Transitive Suffix.

In this context, the xotv specifies that the act of cutting turned one thing into two things, i.e. the man’s neck and the rest of his body.

If we take away xotv, we get this sentence:

11 – 79 Nabbu itevi sernixen. = The knife cut his neck.

In this sentence, the man may still be alive, because his neck, although it has been cut, is still attached to the rest of his body.

In the previous sentence, xotv functions as a semi-equivalent to the English off.

Another example of xotv goes thus:

11 – 80 Rutexotxotvi. = The two of them cut it into pieces.

This one-word sentence is built from five components:

- ru- = the 3rd Person Dual Subject Prefix.

- te = a Verb which means cut.

- xot = a Partial Reduplication of the following component.

- xotv = a Verb which means break.

- -i = the Transitive Suffix.

te and ta are both alternative forms of the Verb tev.

In this context, the Reduplication of the Verb xotv indicates that it was done multiple times in a single moment; or that the moment was peculiarised, distinguished from other moments, by the amount of cutting which takes place therein.

Pearce also includes some examples of xotvi which come from Scripture. Here are two such sentences:

11 – 81 Vetox nen bburxotvi go iravi vex jixi arres sen rin. = After that he broke it and gave it to his men. (Matthew 26:26)

11 – 82 Naboŋ iŋot arres rajari xini xini ginxe ŋa miterter go imovasxotxotvi. = For many days people tied him with strong rope, but he always broke it. (Mark 5:4)

In the first example, xotvi combines with bbur, which means meet.

In the second, the partially Reduplicated xotxotvi combines with vas, which means make.

One wouldn’t think that xotv could combine with Verbs which seem to have the exact opposite meanings. This will give me plenty upon which I can chew.

In this section, we shall finally explore the topic of Negation in and of itself.

Unua has three structures which indicate Negation, and these differ largely on strength. Thus

Weak: b-…seb

Medium: b-…seb-… rre

Strong: t-…seb-… rre

As mentioned earlier, but collected into one place here: bV- is the Irrealis Prefix; seb- / sebe- is the Negative Prefix (although in Weak Negation it appears as a Suffix); tV- is the Definitive Negative Prefix; and rre is the Negative Post-Verbal Particle.

However, it should be noted that the Irrealis Suffix can be replaced by the Relative Suffix m-. For example:

11 – 83 Imrebe musebrarjej se rre toŋo bimre ŋa xina mararjej se xai? = Why do you not have pity on him as I have pity on you?

Here, the important Noun phrase is imrebe musebrarjej se rre toŋo, which is the part of the sentence which means why do you not have pity on him?

imrebe is an Interrogative word which means how, or in this case why as in the sense of how is it the case that…

musebrarjej is built from four components:

- m- = the Relative Prefix.

- u- = the 2nd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- seb- = the Negative Prefix.

- rarjej = a Verb which means pity or have pity.

se and rre are the Genitive and Negative Particles respectively, whilst toŋo is a Singular Person Demonstrative. Thus, a more literal translation of this Phrase goes:

11 – 84 Imrebe musebrarjej se rre toŋo? = Why do you not have pity on the person?

Before we undertake a quick excursion concerning the Relative Prefix, I shall briefly recount the 33rd Verse of the 18th Chapter of the Gospel of St. Matthew, which goes thus: Shouldest not thou also have had compassion on thy fellowservant, even as I had pity on thee?

In Unua, the Relative Prefix m-. In English, it is almost always translated through the use of a Subordinate Clause. In this capacity, it almost always preceded by the Complementiser ŋa.

For example:

11 – 85 Teme mende ŋa mutox re mamiren. = Our father, who art in Heaven.

The Noun Phrase ŋa mutox is built from four components:

- ŋa = the Complementiser Particle.

- m- = the Relative Prefix.

- u- = the 2nd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- tox = a Verb which means stay.

By itself, ŋa mutox translates to who art, or that art, depending on the translation.

In Pearce’s Grammar, however, who art is replaced by who is. Not only would it take too long to explain the significance of this change, it is probably above my expertise.

In addition, the Relative Prefix typically follows imrebe (how), but there are examples which do not, for example:

11 – 86 Uvena imrebe? = How did you come?

uvena is built from two components:

- u- = the 2nd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- vena = a Verb which means come.

In addition, imrebe is, itself, built from two components:

- i- = the 3rd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- mrebe = a Verb or Adjective which means how.

Thus, imrebe has a literal translation someway akin to it is how or how is it. I do not know whether mrebe ever appears with a different Subject Prefix.

In this section, we will briefly explore xise, also known as the X-Genitive.

In most contexts, it acts as an alternative to se, although it is most typically used when indicating the place whence a person comes. For example:

11 – 87 Xina xise Batabbu. = I am from Batabbu.

In this context, xise translates directly as from, though the alternative of is available to one who wishes to sound more eccentric.

The alternative xina se Batabbu is equally acceptable.

However, Pearce notes that most instances of xise come from the New Testament translations, and rarely in the recorded speech data.

In the New Testament, xise is extensively used to indicate one with whom an individual is associated. For example:

11 – 88 Go angel soxa xise Atua irexmari vex jixi rate. = And an angel of God appeared to them.

The relevant Noun Phrase angel soxa xise Atua is built from the following:

- angel = a Noun which means angel.

- soxa = the Number one.

- xise = the X-Genitive Particle.

- Atua = the word for God.

Before we continue, we will quickly dissect the Particle jixi, which has two components:

- ji = the Directional Particle, which we discussed earlier.

- -xi = the Oblique Suffix.

Earlier we discussed the Oblique Marker in its various forms.

As a Suffix, it typically takes the form –xi, and jixi is a common combination.

Similar to the regular Genitive se, the X-Genitive xise can also take the Singular Possessive Suffixes. Examples thereof include:

11 – 89 Namij xisog isebemirr rrob bivo. = My banana is not yet properly ripe.

11 – 90 Nani xisom imermervur. = Your coconut rolled away.

In order to have them written down, the 1st and 2nd Person Singular Possessive Suffixes are –g and –m respectively.

For some reason, they typically turn a final /e/ into an /o/, and this appears to be the case with se also.

11 – 91 Matxorxor xisen ise. = His sling snare is no good.

The 3rd Person Singular Possessive Suffix is –n, and it has no effect on the final vowel of the suffixed word.

In addition, ise is built from two components:

- i- = the 3rd Person Singular Subject Prefix.

- se = a Verb which means be bad, or an Adjective which means bad.

It seems that se managed to sneak an extra appearance into our example sentences, the cheeky devil.

The Scripture used earlier was from the 2nd Verse of the 9th Chapter of the Gospel of Luke, which goes: And, lo, the angel of the Lord came upon them, and the glory of the Lord shone round about them: and they were sore afraid.

In our final section, we shall explore the Verbs nog and kas, whose peculiarising distinction goes into questions of interpretation and intended meaning.

Here is one example involving nog:

11 – 92 Mormajiŋ morxa mornog, go morvena mornon, go morŋavŋav. = When the two of us finished working, we went and we sat down and rested.

With each of these verbs, the Subject Prefix is mor-, this being the 1st Person Dual Exclusive Subject Prefix.

This means that when I say we, you are not included.

One particular section requires some unpacking.

mormajiŋ morxa mornog contains three Verbs:

- majiŋ = work / worked

- xa = go / went

- nog = end / ended

Thus, the literal translation of mormajiŋ morxa mornog is something akin to we worked, we went, we ended, although a better translation goes (when) we finished working.

morvena has been translated as we went, although vena typically means come, so we came is arguably a better translation.

mornon includes non, a Verb which means sit or sit down, whilst morŋavŋav contains ŋavŋav, which means rest.

Here, Pearce makes sure to point out that whilst the current period of work is at an end, there is nothing to prevent me and my friend from starting again at another point.

Now, we move on to our example featuring kas:

11 – 93 Nesur rusursur, rusursur rusursur rusursur rririvji raxa rakaskasi. = The dry coconut leaves were burning and burning and burning completely all around.

nesur is a Noun which means dry coconut leaf.

Appearing four times in a row, we have rusursur, which is built from two components:

- ru- = the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- sursur = a Verb which means burn.

rririvji is a Locational term which means around.

raxa is built from two components:

- ra- = the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- xa = a Verb which means go.

rakaskasi is built from four components:

- ra- = the 3rd Person Plural Subject Prefix.

- kas = a Verb which means complete.

- kas = a Reduplication of the former.

- -i = the Transitive Suffix.

Here, we see one major difference between nog and kas.

Essentially, kas is almost, if not always, followed by the Transitive Suffix –i, whilst nog never carries this suffix.

Now, it is clear from context that, once the coconut leaves have burnt up, they can’t be burnt again, or re-burnt.

Pearce describes this as the difference between the Completive and the Terminative.

kas/kasi is the Completive, it marks the end of a process that cannot be repeated or continued at a later date.

nog is the Terminative: the action has ended but you can come back to it later.

Termination is not the same as Completion.

That being said, in some uses of nog, the context could imply that the action has been completed. For example:

11 – 94 Ale, nowet rrarra apen novjixni nixe ixa ixa inog. = Ok, I waited, I waited, and below the other one went on sticking the sticks until it was finished.

Here, it is ambiguous whether any more sticks could be stuck together.

In addition, there are some activities which use kasi because they have Locational end-points, even if you could continue doing it, for example:

11 – 95 Rijen ŋo ixa ves jixi arres kebeg, itebatin Jerusalem, go bixa bikasi vanu apen. = The message went to all people, it started in Jerusalem and it will go all over the Earth.

The relevant section is bixa bikasi vanu apen:

- bixa = it will go

- bikasi = it will ___ all over

- vanu apen = the Earth

The Noun Phrase vanu apen literally means land below, or the land below.

The message will have completed its journey when it has travelled across the whole Earth, though it could, in theory, extend beyond it.

Furthermore, we have itebatin, which includes the Verb tebatin, which means start.

Before I write down my more general thoughts, I shall briefly quote the 47th Verse of the 24th Chapter of the Gospel of Luke, which goes: And that repentance and remission of sins should be preached in his name among all nations, beginning at Jerusalem.

This is not the final verse of the Gospel of Luke, but appropriately it is not far off.

So what are my thoughts on this language overall?

After spending a few months on the previous Urum article, it was nice to come across a language that makes extensive use of Prefixes. Compared to the Wangkajunga language which we explored in the article before that, these Prefixes were mercifully simple.

This is not the first Austronesian language to come under my gaze, see the article on West Futuna-Aniwa to see another one in action. In fact, both Unua and the above are from Vanuatu, which may explain many of their similarities, more in rhythm rather than lyric.

If I remember correctly, West Futuna-Aniwa also had Trial Number, whilst Unua maintains a relatively simpler Singular-Dual-Plural distinction. Thus far, West Futuna-Aniwa is the only language I have studied which has a Trial Number, but I digress.

On the whole, Unua is probably one of the least intimidating non-European languages for a beginner. It’s quite isolating, though where it uses Affixes, these are highly agglutinative, with each affix encoding just one meaning.

If we exclude reduplications, there are very few verbs built from more than four components. In this sense, it seems a bit boring.

Further, while looking at some of the example sentences from Scripture, we see that there are many instances of mostly 1-to-1 translations. Whilst many newcomers to hard-core linguistics may appreciate this, I prefer the more exotic.

Perhaps I need more challenging fare at this point. We shall see what happens.

(I do not want anyone to think I did not enjoy researching this article. I most certainly did, especially as Pearce’s grammar is incredibly comprehensive.)

Next time, we travel to Central America, where we shall explore the Mayan language of Tzutujil, which I have explored before.

However, this site will be mothballed effective immediately. It shall remain on the internet, but I will no longer upload to it.

I shall continue to be discuss obscure languages on the internet, but I will do so in a different form. It is time for a change, and as I am now a social butterfly who meets his friends in real life, this long-form written content no longer appeals to me.

Also, about a year ago, if not two years ago, WordPress changed the format of its blog composition site, and I still have yet to get used to it. What is now called „Classic“ was simply far superior in terms of usability.

I do not know yet the name of my new Project, but then again, the community of English people wittering on about Tzutujil, Tundra Nenets and Tümpisa is no doubt very small.

If you’ve skipped to the end, I do not look forward to seeing you soon, but if you have read all the way through, then I do (including those penitent good bois and gals who skipped and then went back.)

Sources:

Elizabeth Pearce, A Grammar of Unua (Munich: De Gruyter Mouton 2015)

Malekula Island – An overview – The Barefoot Backpacker (barefoot-backpacker.com)

Nabu – Unua texts (paradisec.org.au)

Google Images

Wikipedia