For those of you who have followed this blog for a while, neither of these languages, especially the latter, require an introduction. For the benefit of new readers, I will briefly explain who each of these languages are.

The Warray language went extinct around the year 2000. During its lifetime it was spoken in the region surrounding the Adelaide River in the Northern Territory. It belonged to the Guwinyguan branch of the Arnhem language family. Further exploration of the language is available in these previous posts:

Warray/Warao Comparison and Warray Verbs

Tundra Nenets, on the other hand, is still alive, with approximately 22,000 speakers. It is spoken in Northern Siberia, roughly opposite the island of Novaya Zemlya, where the Soviets tested many of their hydrogen bombs. Tundra Nenets belongs to the Samoyedic branch of the Uralic language family, and is therefore a distant cousin of several European languages, the most well known of which are Estonian, Finnish and Hungarian. Further exploration of Tundra Nenets is available here:

TN/French and Moody Nenets and others.

Now why are we comparing these two languages, speakers of whom have probably never been aware of the existence of the other?

Well, despite the near certainty that the two have never touched, they happen to share a very interesting feature: The Subject-Object Affix.

What is a Subject-Object Affix, I hear you cry out.

Well, the Affix part is fairly simple. It refers to any combination of consonants and vowels that is attached to a word in order to add further meaning. The most well-known, and probably common forms of Affix are the Prefix, which comes at the start of a word, and the Suffix, which comes at the end.

More obscure examples include the Infix, which goes inside a word; and the Circumfix, which has parts which go at both he beginning and end of a word.

The Subject-Object part, meanwhile, refers to the fact that it tells the listener not only who did the action, but also to whom they did it.

As we will explore below, Warray makes relatively limited use of the Subject-Object Prefix, while Tundra Nenets has a substantially more developed Subject-Object Suffix system.

First, we shall explore how these features manifest themselves in Warray, followed by a focus on its counterpart in Tundra Nenets, and we shall finish with a direct sentence comparison.

(The Tundra Nenets hail from a long tradition of reindeer herders, and many continue to follow this lifestyle to the present day. This may help to explain why, despite the relatively large geographical area over which the language is spoken, dialectical differences are very few.)

Section 1: Warray

Before we discuss the Subject-Object Prefixes, we will first explore Subject and Object Prefixes in turn, which should hopefully give you a good foundation to the rest of the exploration.

Just like any other language, Warray has pronouns. However, these are not used in most simple sentences. Instead, there is a system of Subject and Object Prefixes which one attaches to the beginning of the verb. Here is a table: (Note that this is a simplified version of the table that appears in Mark Harvey’s Grammar)

In Warray, there are two semantic classes of verbs. These are the Stative, which describe states of beings, and the Active, which describe actions.

For Stative verbs, the Complete/Non-Complete distinction produces a division between the Future and Non-Future Tenses.

An example of a Stative Verb is ngantitepmal, which means to be thirsty. In the below sentences we will use the Realis conjugation of ngantitepminj.

1st Person Plural:

manmangantitepminj = We will be thirsty

mangantitepminj = We are thirsty / We were thirsty

3rd Person Singular:

ngantitepminj = He or she will be thirsty

kangantitepminj = He or she is thirsty / He or she was thirsty

In addition to the Subject Prefixes, we also have the Object Prefixes, which are much simpler.

For Active verbs, the Complete/Non-Complete Subject Pronoun Division leads to a Past/Non-Past distinction.

Here we will study the verb pemal, which means to shake, and whose Realis Conjugation is peminj.

2nd Person Singular Subject with 1st Person Plural Object:

pananpeminj = You shook me

panankapeminj = You are shaking me / You will shake me

1st Person Singular Subject with 3rd Person Plural Object:

atpunpeminj / atputpeminj = I shook them

patpunpeminj / patputpeminj = I am shaking them / I will shake them

In Warray, Subject and Object Prefixes follow a certain order, which is as follows:

1st Person Subject – Object – 2nd Person Subject – ka- – pa- – kan-

I am afraid that this is something that you will need to memorise. If anyone can come up with a trick that helps people to remember it, I would be interested to hear it.

Hopefully, this should give you a sufficient background understanding of how Subject and Object Prefixes function.

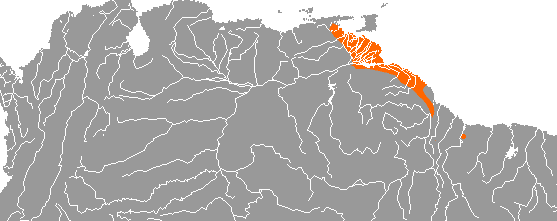

(Warray is a member of the Guwinyguan branch of the Arnhem Land Language family, which is represented in purple on the map. The white spaces represent the Pama-Nyungan languages, the grep spaces the other non-Pama-Nyungan languages, and the other colours represent the other branches of the Arnhem Land family.)

Section 2: The Warray Subject-Object Prefixes

In a limited number of circumstances, Warray offers a single prefix which encodes both the Subject and Object of the verb. These cannot be broken down into smaller components. They are as follows:

The Realis conjugation of tumtjitmal is tumtjitminj, which means to be jealous of someone.

parinjtumtjitminj = I will be jealous of you

arinjtumtjitminj = I am jealous of you / I was jealous of you

punminj is the Realis conjugation of punmal, which means to bury:

inipunminj = We buried you (all)

paninipunminj = We are burying you (all) / We will bury you (all)

Naturally, there is more to the Warray Subject-Object Prefix than what we have discussed here, though in the interests of time we will briefly end it here in order to introduce the second language under investigation.

(Two Forest Nenets women take a walk through the woods. Forest and Tundra Nenets are considered either as sister languages or dialects of the same language. Ultimately, despite the relationship between the two languages, they share low mutual intelligibility. If I find any comprehensive information on this language then we many well explore it in a later issue.)

Section 3: The Tundra Nenets Subject-Object Suffix

Before we begin, it bears pointing out that Tundra Nenets does not lack for Subject-Object Suffixes. However, for the purposes of your sanity, we will only discuss the Imperative Mood Suffixes, although most other suffix tables tend to follow the same pattern.

The Imperative Mood is used for giving commands, e.g. do this! or do that!

Here are some examples of these suffixes in action, all of which are built using the verb ləxonako, which means to talk:

s’iqm’i ləxonakor’ih = Talk to me, both of you!

s’idon’ih ləxonakoxəyudaq = Do talk to the both of us, all of you!

s’idonaq ləxonakonoq = You there, talk to us!

s’iqm’i is the Tundra Nenets word for me.

s’idon’ih and s’idonaq both translate into English as we; the former refers specifically to two people and the latter refers to three or more people.

-r’ih is the 2nd Person Dual Subject > Singular Object Suffix, which refers to a command for two people to act on a single object.

-xəyudaq is the 2nd Person Plural Subject > Dual Object Suffix, which refers to a command for more than three people to act on two objects.

-noq is the 2nd Person Singular Subject > Plural Object Suffix, which refers to a command for exactly one person to do something to three or more objects.

The main thing worth noting here is that Tundra Nenets has a Singular-Dual-Plural distinction, whereas Warray possesses a Singular-Plural distinction. (There is some evidence that Warray may have once had a similarly, if not more, developed Dual distinction. However, Mark Harvey reports that many of the Warray had forgotten their original language, and thus much of the language will likely never be known.)

Now that we have explored each language individually, now it is time to compare and contrast these two languages directly.

(The Adelaide River is home to the jumping crocodile, which seem happy to jump up for the pleasure of tourist and their cameras. Let’s hope that the organisers keep them well fed.)

Section 4:

In this section, we will analyse a number of sentences, and how they are different across our two languages. I would wager that this is the first time that anyone has ever compared and contrasted these two languages, and therefore you shall see history unfold before your very eyes.

English: Carry her through the gate alone! / Carry him through the gate alone!

Warray: ngantiwulmapwuy antjim

Tundra Nenets: s’it’a n’owona n’ūp’iwado

First of all, neither Warray nor Tundra Nenets possesses a distinct word meaning gate.

In Warray, we have antjim, which means mouth.

The Tundra Nenets word n’o means door. Interestingly, the Tundra Nenets word for mouth is the rather similar n’ah.

ngantiwulmapwuy is built from two components. The first is ngnatiwulma, which is the Imperative form of ngantiwulmal, which means to carry.

In contrast to Tundra Nenets, the Warray Imperative Prefixes are rather simple. The Object Prefixes are the same as those discussed above.

Meanwhile, if you are ordering a single person, you do not add a prefix. In you are commanding more than one person, one adds the prefix pa-.

Therefore, if I wanted to command several people to carry one person, I would instead utter pangantiwulma, and I f I wished to change who was/were being carried, the above mentioned prefix order would once again apply.

As a result, ngantiwulma takes zero suffixes, which means that it refers to a Single Subject acting on a Single Third-Person Object. Without further context, this 3rd Person Object could translate into English as he, she or it.

In contrast to Tundra Nenets, Warray actually does possess a distinction between he and she, these words being akala and alkala respectively. However, in a simple sentence such as this, it is not necessary to include them, and therefore the distinction no longer applies here.

-pwuy is the Perlative Suffix, which is used to indicate motion either along or through a place.

Now for the Tundra Nenets sentence:

s’it’a is the 3rd Person Singular Accusative, thus it means both him or her.

Attached to n’o is the Perlative Suffix -mən’a, which takes the reduced form -wona when it occurs after a vowel. (Note, in the publicly available grammar this is referred to as the „Prolative“ as oppose to the „Perlative“.)

n’ūp’iwado is formed from n’ūp’iwa, which means to carry, and –do, which refers to a single person acting on a single object.

Across the world, the Perlative case is a rare feature, appearing predominantly, though not exclusively, in Australian Aboriginal languages as well as those found in the far north of America, e.g. Inuktitut and Eurasia, e.g. Chukchi.

(A map displaying all of the languages, both past and present, spoken within the northernmost point of the Northern Territory. This is not only the most linguistically diverse part of Aboriginal Australia, possessing a greater variety of language families than the rest of the continent, but one of the most linguistically diverse places in the entire world. This is coupled with the fact that it lies not far away from Papua New Guinea, the single most linguistically diverse place in the world by far.)

In conclusion, I hope that you have enjoyed reading of a comparison between two languages whom no one would have ever thought to compare. Naturally, we have barely begun to scratch the surface of either language, and I encourage you all to explore them at your own leisure. What I rarely, if ever, mention is that almost to every resource that I use was publicly available, at least at the time when I downloaded it.

For our next exploration, I feel that it is time to return to Papua New Guinea, an island roughly twice the size of the author’s native Great Britain, but with more than 800 indigenous languages, more than any other single country on Earth.

In a previous article I discussed a particularly interesting feature of the Manambu language, in particular how the word for testicles can also mean under. There is little to no doubt that I can probably find another feature worthy of discussion. Until then,

Same Wilf-Time!

Same Wilf-Channel!

Sources:

Irina Nikolaeva, A grammar of Tundra Nenets (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH 2014)

Mark Harvey, Ngoni Waray Amungal-Yang: The Waray Language from Adelaide River (Australian National University 1986)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Warray_language

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tundra_Nenets_language

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Macro-Gunwinyguan_languages

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forest_Nenets_language

Google Images