In the first of what will hopefully become a semi-regular series, I will compare two languages who share nothing more than confusingly similar names. By this, I mean that the names of the languages will differ by rarely more than three letters.

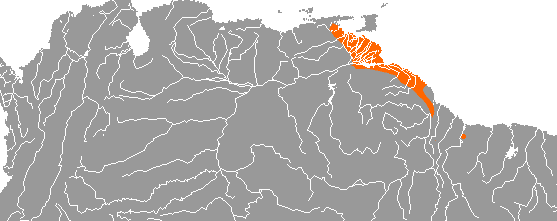

In alphabetical order, our first language is Warao, a language isolate spoken by around 33,000 in the Orinoco Delta of north-eastern Venezuela, alongside smaller communities in the nearby countries of Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana and Suriname. (If you would like a more concise introduction for the Warao language, feel free to watch the video in the source link. It was this same video that initially introduced me to the language.)

Currently, Warao has no known linguistic relatives, with one possible exception, this being the Timucua language. Aside from any grammatical features, the main problem with any link between these two is that Timucua was spoken in northern Florida, which no further sister languages in between, whether via land or across the Gulf of Mexico.

Furthermore, the language went extinct during the second half of the 18th century. Despite this, there is a wealth of information on the language, most of which comes from the work of Franciscan Missionary Francisco Pareja.

(The area wherein Warao is spoken.)

Warray was an Arnhem-language spoken in and around the Adelaide river in the Northern Territory of Australia. It went extinct somewhere around the turn of the 20th century.

In the language grammar I used, the language name is spelt Waray. I chose the above spelling with two /r/’s in order to make the two languages more distinct.

In addition, my original plan was to compare Warao to the Waray language of the Philippines. This changed after I found the Warray grammar which I reference in the source list. In truth, I had been unaware of the language’s (former) existence.

Also, by establishing this spelling convention at the earliest possible time, I allow myself more freedom to one day compare Waray and Warray.

For full disclosure, I may have been hasty in choosing this comparison, in the sense that I could have done further research before committing myself to this topic. Nevertheless, I have committed myself to this endeavour, and will persevere.

(The Warray language belongs to the Guwinyguan branch of the Arnhem language family, which is shaded in purple in the above diagram. Grey indicates other Non-Pama-Nyungan languages, white indicates the Pama-Nyungan language family, while the other colours refer to other branches of the Arnhem family.)

Sentence 1.

English: A snake bit me

Warao: ma huba abuae / huba mabuae

Warray: tjun panpe

ma is the 1st Person Object Pronoun, which translates as me. It can occur as both an Independent Pronoun, and also as the prefix m- or ma-, the form which it takes in the second version of the sentence.

huba means snake. Based on what information I could find, there seems to be only one word for snake in Warao. This is not the case in Warray, as we shall explore.

abuae means bit. To build this short word, we start with the root verb abu, which means to bite.

Our first Suffix, -a, is defined as the Punctual Aspect, which defines the event as one that took place in a single instant. This aspect is typically defined as a Semelfactive, or an aspect that relays the flow of time in the form of a verb stem.

Our second suffix, -e, is simply the Past Tense Suffix.

A literal translation:

ma huba abuae / huba abuae = me snake bit / snake me.bit

(A traditional open-sided Warao hut on stilts. The Warao were one of the tribes encountered by the explorer Alonso de Ojeda, who travelled with (in)famous explorer Christopher Columbus. Upon seeing structures similar to those pictured above, he named the village and the surrounding area Little Venice or, Venezuela, in his native Spanish. This is, as far as can be told, the origin for the name of the modern country.)

Despite how different these two sentences look at a superficial level, structurally they share a number of similarities. Let us explore.

tjun means Children’s Python, though there does exist a generic word for snake, which is pelam.

panpeminj is a a four-part word which, taken together, translates to bit.me.

We begin with the verb root pe, which means to bite, to which we add a single prefix.

This prefix is pan-, which is the First Person Singular Object Prefix, which translates to me. As far as I can discern, Warray does not seem to possess any independent Object Pronouns.

In Warray, there are 8 separate regular verb conjugations, not all of them we will be able to discuss in this article. The verb pe belongs to the simplest of these conjugations, in that it takes the fewest suffixes. It is also an Active verb, as oppose to a Stative verb, a distinction whose importance we shall discuss shortly.

Unlike most Warray verbs, the Realis conjugation for pe is the same as the infinitive. By this, it does not take any suffixes for the Realis Mood.

The Realis Mood is used to indicate that the sentence is a statement of fact. This mood exists in English, where does not require any particular marking (i.e. a normal sentence).

However, to fully explain this sentence, I must draw your attention to a prefix that does not exist, namely the 3rd Person Singular Complete Subject.

Although Warray does possess independent Subject Pronouns, these are not mandatory in every sentence due to the presence of the Subject Prefixes, which precede the Object Prefixes whenever they occur.

For each person, there are three categories of Subject Prefix, the Complete, the Non-Complete and the Potential (though we will only explore the first two.)

One thing that Warray lacks, as far as I can see, are regular Tense markers. It is for this reason that the Subject Prefixes come into their own.

In an Active verb, the choice between a Complete or a Non-Complete distinction is equal to a Past/Non-Past distinction. Because we are using the Complete Suffix, the sentence takes place in the Past.

If we were to replace this with the Non-Complete Suffix, -ka, then the sentence takes place in either the Present or the Future. For example:

tjun pankape = the Children‘ Python bites me / the Children’s Python will bite me

A word-for-word translation:

tjun panpe = Children’s-Python me-bit

As is the case in Warao, the Warray pronoun is prefixed to the verb. However, the difference here is that in Warao, this prefixation is optional, whereas Warray provides no alternative.

(Antaresia childreni, also known as the Children’s Python. Although it is named after British Zoologist John George Children, it is arguably one of the most appropriate snakes to buy as a pet for one’s children. It does not produce venom and is, in terms of diet, relatively undemanding compared to other species.)

Sentence 2.

English: I run through the forest / I will run through the forest

Warao: inabeya ine hayate / inabeya hayateine

Warray: marelik patliliminjpwuy

In this example, we will see a greater convergence between the grammars of these two languages. Let us begin, as before, with the Warao sentence.

inabeya is the Allative Case Declension of inabe, which means forest.

The Allative Case Suffix, -ya, in Warao is used to indicate movement either towards or through a place.

ine is the 1st Person Singular Subject, or I.

hayate is the Non-Past Tense inflection of haya, which means to run.

-te is the Non-Past Tense Suffix, which means that it can indicate either the Present or Future Tense.

-ine, which appears in the second Warao sentence above, is the 1st Person Singular Subject Suffix.

In Warao, a Subject Pronoun can take the form of either a Suffix or an Independent Word, though you can’t have both in the same sentence together.

Furthermore, you may have noticed across both sentences that the Word Order in Warao seems to be Object-Subject-Verb (at least when all three occur as independent words). This is no stylistic choice, as Warao possess the least common (default) word order in the world, behind only Object-Verb-Subject. Between them, these two word orders comprise approximately 1% of the world’s languages.

(Two Warao men engaged in building a traditional canoe. The name Warao itself even means „boat people“ after their deep connection with the water.)

marelik is the Locative Case Declension of mare, which means forest or jungle.

The Locative Case, as the name suggests, indicates location.

patliliminjpwuy is a word with much to unpack.

First, we start with lili-m-inj, which is the Realis Conjugation of lili-m-al, which means to run. It is accompanied by one prefix and one suffix.

pat- is the 1st Person Singular Non-Complete Subject Prefix. In the presence of an Active Verb, it refers to the Non-Past Tense, i.e. it can refer to either the Present or Future Tense.

-pwuy, meanwhile is the Perlative Case Suffix, which only attaches to verbs.

The Perlative Case refers to movement along, through or across the noun to which it is attached. Because this suffix is attached instead to the verb, the noun therefore requires the Locative Case Suffix.

The Perlative is among the rarest of cases. It only appears in a number of Australian languages, Inuktitut and the Aymara language of South America. It was also present in the now extinct Tocharian Branch of the Indo-European family.

(A stretch along the Adelaide River, highlighting the tenor of forest through which the Warray would run. It bears pointing out that Warray is not a language of the Outback.)

Sentence 3.

English: We have three sisters

Warao: rakoi dihanamo (oko) ha

Warray: alwulkan kerangantjerinj palikakangi

In Warao, the hand signal for the number 3 involves the forefinger, middle finger and ring finger. This is because, according the grammar, the „group of fingers that gets together with ease“, and thus does not experience the „natural resistance to cluster observed in the distal units: the thumb and the forefinger“.

I felt it was of crucial importance that you know the Warao hand gesture for this particular number.

The Warao word for three is dihanamo.

rakoi means sister in the Singular. Due to the presence of dihanamo, it does not take the Plural Suffix -tuma, which it would if there were an indeterminate number of sisters.

oko is the 1st Person Plural Pronoun, i.e. we. It is included in brackets since it is not always mandatory to include, e.g. if it comes after a question.

In Warao, there are only two grammatical numbers, the Singular and the Plural.

ha, meanwhile, is the Copula. It is used to link between the subject of a sentence and a complement, e.g. an adjective. The equivalent in English would be the word is.

(The Warao people and their boats in action.)

alwulkan means sister, and is the Feminine Declension of wulkan, which means sibling.

The Warray language has two Human Class markers, Masculine and Feminine, and only occur on nouns that refer to humans. The word for brother is awulkan.

kerangantjerinj means three.

palikakangi is composed of three components.

kangi is the Realis Conjugation of kangi, which means to take, though here it means to have, and is preceded by two prefixes.

The first of these prefixes is pali-, which is the 1st Person Plural Non-Complete Subject Prefix, a close approximant to the English we.

It is worth noting that Warray Subject Pronouns also exist as independent words, though they are only used under other conditions.

Warray, like Warao, also has a distinction between the Singular and the Plural. In addition, it also distinguishes the 1st Person Dual Inclusive, i.e. the speaker and the listener. However, this is the only instance of either the Dual Number or the Inclusive/Exclusive Dichotomy within the Subject Prefixes.

The second prefix ka-, is merely a Reduplication of the first syllable of kangi. The function of reduplication in Warray is a complex one, made even more complicated by Language Death, a phenomenon in its own right.

(A Jumping Crocodile in Adelaide River. In Warray, anmaymak:u means freshwater crocodile and apulangu means saltwater crocodile.)

In conclusion, I hope that this was an interesting introduction to and comparison between two languages with confusingly similar names, otherwise separated by thousands of mile of ocean and, sadly, the mortal coil. If either of these languages fascinated you, I more than encourage you to do your own further research.

As mentioned earlier, this format of comparing languages whose names only differ by a single letter or two is one to which I plan to return in the future, though it won’t become too regular a feature.

Naturally, I do intend to delve into further detail on both of these languages, though time will tell how this will be done.

In our next installment, we will discuss pronouns in the Unua language of Malekula Island, Vanuatu, and how they are more specific than their English counterparts. Until then,

Same Wilf-time!

Same Wilf-channel!

Sources:

Andrés Romero-Figeroa, A Reference Grammar of Warao, (München: LINCOM GmbH 2003) 2nd printing

Mark Harvey, Ngoni Waray Amungal-Yang: The Waray Language from North Adelaide River (Australia: Australian National University 1986)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Warray_language

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Warao_language

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semelfactive

http://www.whatsnakeisthat.com.au/category/region/nt/north-nt/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Children%27s_python

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Macro-Gunwinyguan_languages

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Warao_people

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perlative_case